The Dallas Fed announces a conference on the topic I’ve been writing about lately — namely, the intersection of globalization, capital flows, asset prices, China, and monetary policy.

“Alexander Hamilton was right”

Steve Forbes with a resounding call for stable, low-entropy money.

Greenspan truly began to think he was a monetary philosopher king who could fine-tune economic activity by manipulating short-term interest rates. Greenspan’s Louis XIV “I am the state” proclivities were intensified when he fell under the sway of a strange theory of Ben Bernanke’s. Bernanke joined the Fed as a governor in 2002 and posited that the world was plagued by “excess” savings. China, India and other countries were saving too much money. Preposterous! In a properly functioning global financial system there can be no excess savings. The whole purpose of finance is to direct savings from one party to be invested with another party. The enormous amounts of liquidity that led to the housing and commodities bubbles of recent years cannot be blamed on thrifty Chinese but on the excess money creation of Greenspan and Bernanke. If their central goal had been a steady value for the buck, those bubbles would never have reached the sizes they did, and volatility in the financial markets would have been only a fraction of what it is today.

Here’s Forbes making the point from Davos.

China, the Dollar, and the Crash

See my latest on the nexus of China trade, monetary policy, and our current crisis in Monday’s Wall Street Journal. Contrary to the new conventional wisdom, which is gaining considerable steam, I argue that:

America did not underreact to the supposed Chinese threat. It overreacted. The problem wasn’t “global imbalances” but a purposeful dollar imbalance. Our weak-dollar policy, intended to pump up U.S. manufacturing and close the trade gap, backfired. Currency chaos led to a $30 trillion global crash, an energy shock, bank and auto failures, and possibly a new big government era. For globalization and American innovation to survive, we must first understand the Chinese story and our own monetary mistakes.

A “more competitive currency” and monetary “stimulus” cannot create new wealth. Only technology and entrepreneurship can do that. The “China currency” issue distracts America from all the important things that could actually make us more competitive –e.g., better K-12 education, much lower corporate tax rates, cutting-edge broadband networks, less (not more) centralization and power in Washington, and, of course, a stable dollar.

The euro at 10

Excellent summary on the euro currency’s first decade of life:

As important, the creation of a single European Central Bank (ECB) has better insulated monetary policy from political manipulation. Politicians could no longer attempt to inflate their way out of their employment or fiscal problems. National central banks could no longer finance fiscal deficits, removing a source of economic instability.

The single economic space anchored by the euro has also forced European policy makers to compete for people, goods and capital with improved policies. While we had hoped to see more reform by now, the pan-European reduction in corporate tax rates is one fiscal benefit of the euro. Even Germany has cut corporate taxes, after its efforts to harmonize rates across the European Union failed.

The Real China Story

The New York Times, in its series on the origins of the financial crisis it calls “The Reckoning,” pins our housing and credit bubbles on Chinese savings and the U.S.-China trade gap. This is basically the view of Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke. We were helpless. Monetary policy had become ineffective. The New York Times also says the U.S. failed to react to the China-U.S. “imbalances” soon enough, that we took a “passive” approach.

In fact, most of this is backward. We did not under-react to China. We overreacted. The U.S. weak-dollar policy — a combination of historically low Fed interest rates and a Treasury calling for a cheaper currency — was a direct and violent reaction to the trade gap. A series of Treasury secretaries and top U.S. economists, from John Snow and Hank Paulson to John Taylor and Martin Feldstein, explicitly backed this policy as a way to “correct” these “imbalances.” This weak-dollar policy was designed to reduce the trade gap but in fact boosted it by pushing oil and other commodity prices through the roof. It also created and pushed excess dollars into other hard assets like real estate, resulting in the housing boom and then bust.

America’s overreaction to China’s rise in particular and our misunderstanding of global trade and finance in general was thus, I believe, the chief source of our current predicament. The Fed and Treasury failed to grasp the truly global nature of the economy and the centrality of the dollar around the world. I tell the story of Chinese-U.S. interaction in this long paper, “Entrepreneurship and Innovation in China: 1978-2008.”

Bold Ben

I’ve been a harsh critic of the Greenspan-Bernanke monetary policy that was the chief cause of our current economic mess. But it’s also true that, once the financial firestorm hit, Ben Bernanke, perhaps the world’s leading student of financial crises, has taken bold and creative action to douse it. Nobel laureate Bob Lucas thinks Bernanke is on the right track:

monetary policy as Mr. Bernanke implements it has been the most helpful counter-recession action taken to date, in my opinion, and it will continue to have many advantages in future months. It is fast and flexible. There is no other way that so much cash could have been put into the system as fast as this $600 billion was, and if necessary it can be taken out just as quickly. The cash comes in the form of loans. It entails no new government enterprises, no government equity positions in private enterprises, no price fixing or other controls on the operation of individual businesses, and no government role in the allocation of capital across different activities. These seem to me important virtues.

Have the dollar devaluationists learned nothing?

Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson is back at it. Having presided over the debasement of the U.S. dollar, he is once again cajoling the Chinese over the value of its currency, the renminbi (or yuan). Paulson earns a few points for his semiannual Special Economic Dialogue that has facilitated U.S.-Chinese cooperation on some fronts and helped defuse some of the worst protectionist policy on both sides. But the Greenspan-Snow-Bernanke-Paulson weak dollar policy — which was in itself deeply protectionist, and ultimately highly self-destructive — utterly swamped any of Paulson’s good intentions vis-à-vis China.

Digging through some old files, I found a May 13, 2006, e-mail I wrote to a senior White House economic official, warning of the certain harmful effects of its weak-dollar policy. (I had, six months prior, met with the official in the West Wing to discuss the matter.) The morning of my e-mail, The Wall Street Journal, citing top Administration officials making clear their weak-dollar preference, had published a major story: “U.S. Goes Along With Dollar’s Fall to Ease Trade Gap,” with the subhed, “Quiet Acquiescence Holds Possible Risks for Economy; Surge in Exports in March.”

The previous week economist John Taylor, just off his post as Treasury Undersecretary, had, in another Wall Street Journal article, dismissed the views of Nobel laureate Robert Mundell and Stanford economist Ronald McKinnon. Mundell and McKinnon had been arguing against dollar weakness and urging dollar-yuan stability. Taylor’s offensive, moreover, had been previewed by yet another two articles, one from Martin Feldstein and another from Lawrence Lindsey, arguing for a “more competitive” dollar. That’s a euphemism for weak, as in competitive devaluation. (See, not supposed to happen in America).

Written in the heat of battle, I think my e-mail memo holds up pretty well:

From: Bret Swanson <bret.swanson@********.com>

Date: Sat, May 13, 2006 at 1:38 PM

Subject: stunning protectionist mercantilism

To: [senior White House official]*** Warning: Blunt Statements to Follow ***[senior White House official],

Even considering Treasury’s misguided currency stance these past few years, today’s news in the Journal that the White House approves of the further weakening of an already too-weak dollar is stunning and alarming.Using monetary policy to target the trade deficit instead of using monetary policy for its only legitimate purpose of price stability and currency stability, is massively irresponsible. The trade deficit is a mostly meaningless accounting number that if anything demonstrates the strength of the American economy, not its weakness. “Competitive devaluation” is what Third World nations did for decades. It’s what helped keep them poor. It’s what we did in the 1970s, a lost decade of malaise. In an era of globalization, currency devaluation is more damaging than ever when there is more cross-border trade and investment and a larger proportion of inputs into our final products and services come from abroad.

An already inflationary dollar will become more inflationary. Oil prices will rise further. Recession in 2007 now becomes a real possibility because the Fed will likely now overshoot on interest rates to combat inflation that they and Treasury created but which they never see until it’s too late. Why are we risking ruin of a robust economy?The best economists I know are alarmed at the Fed’s lack of vigilance and the deepening of Treasury’s weak-dollar policy. Having now lost faith in the Fed and Treasury, these economists have changed their outlooks for the U.S. economy from positive to negative.

Lindsey and Feldstein are 180-degrees wrong on monetary/currency/trade policy. Clearly their recent Journal articles were a set-up for this potentially disastrous currency move. John Taylor’s statements last week pooh-poohing Mundell and McKinnon — who are absolutely right on China — were equally discouraging. Not since Richard Nixon have Republicans stood for debasing the currency. It’s painful to agree with those who say this may be the most protectionist Administration since Herbert Hoover.The U.S. Auto Companies and manufacturers want a weaker dollar — manufacturers always do — but the dominance of the Japanese auto makers is not a currency issue. Japan has just come out of a decade of deflation — the yen was way too strong, not artificially weak — exactly the opposite of what the auto makers say. Manufacturers in general face a huge challenge from China, but not because of the yuan, which is exactly in line with the dollar. The China challenge is real, not monetary. The U.S. must become more competitive via lower tax rates and less regulation. Currency is nothing but a scapegoat, and focusing on it reduces the chances we can solve our real competitive disadvantages on taxes and regulations. Because changing the unit of account cannot change the terms of trade, debasing the dollar does not make us more competitive; it makes us less competitive because it fosters inflation and possibly recession.

Furthermore, autos and manufacturing are a shrinking portion of our economy, and this misguided protectionist policy at their behest is highly damaging to the real, growing, leading edge sources of American wealth and power: our prowess in technology, finance, and entrepreneurship.Please forgive my blunt statements. I make them with respect and concern for the success of this White House. I know you can’t comment on currency matters, but if I am overreacting or wrong on my interpretation of what appears to be happening, please let me know.

Very best,

Bret

I then sent the following warning to a number of friends at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, who had been seeking my views:

From: Bret Swanson <bret.swanson@*******.com>

Date: Sat, May 13, 2006 at 2:26 PM

Subject: ALERT: stunning protectionist mercantilism

To: [U.S. Chamber officials]ALERTI believe the outlook for the U.S. economy could be shifting. An article in this morning’s Wall Street Journal makes clear that instead of reversing the dollar’s decline and inflationary pressures, the White House and the Fed are actually encouraging a further fall of the dollar. Amazing. This means more inflation, a potential Fed overshoot on interest rates, and a slow-down and possible recession in 2007. None of this was necessary. We’ve had a very robust economy since mid-2003, and it could have easily continued. Debasing the dollar in a misguided protectionist attempt to reduce the trade deficit is hugely counterproductive. I warned of this possibility in my February memo but held out hope that the Fed and Treasury would reverse its inflationary/weak-dollar course in time to blunt these effects. No such luck.

What this means: The Chamber should prepare for a slow-down/recession in 2007-08. We should prepare for an inflationary environment. This policy means gas prices will probably stay high or go HIGHER. Some auto and manufacturing companies could benefit in the very short term, but overall this is bad for the larger economy, especially for technology and financial firms and for entrepreneurs. When the Fed figures out what’s going on, it will have to raise interest rates more than if it had gotten ahead of the curve in 2004-05. Commodity based businesses will continue to do well for a while, with intellectual property based businesses being hit the hardest. Eventually a recession would hurt everyone.Currency volatility will also discourage international trade and investment, which could lead to slower global growth.

I’ll continue to think about what this means and how the Chamber should prepare.

Best,

Bret

Most of this scenario came to pass. Oil and commodity prices rocketed. Subprime loans, fueled by easy weak-dollar credit, kept flowing through 2006 and 2007. And the U.S., we now know, hit recession in “2007-08.”

Only the mechanism was a bit off. With elevated inflation, real interest rates never got very high — certainly not to the point that normally causes recessions. But the bursting of the adjustable-rate housing bubble, enabled by weak-dollar easy money, and the ensuing credit crisis had the same effect as a high real Fed Funds rate.

Many of the easy money mistakes had already been made by the Fed in 2003-2005. But this crucial period in 2006, when the U.S. government doubled down on a misguided weak-dollar strategy, told foreign capital to stay away, directly devalued all dollar assets, accelerated the financial collapse, and destabilized the globe.

Please, Mr. Paulson, enough with the currency lectures.

(You can find a much more detailed history of the whole era within this longish economic history of China (1978-2008) or this shorter article.)

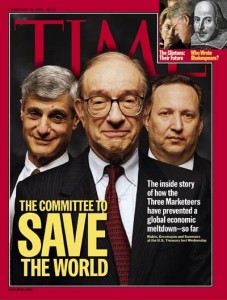

Committee for Self Promotion

Robert Rubin famously was part of the “Committee to Save the World,” so dubbed by Time magazine, as he, Alan Greenspan, and Larry Summers supposedly prevented the Asian flu of 1997-98 from spreading around the globe.

But finally — finally — the mainstream press is wondering whether Rubin’s reputation over the years was justified. From today’s Wall Street Journal:

Mr. Rubin’s salary made him one of Wall Street’s highest-paid officials — and a controversial figure among Citigroup shareholders and some executives, who questioned whether his limited duties justified the big paydays.

“Even though he has no ‘operating’ responsibilities, he still has a fiduciary responsibility as a board member,” said William Smith, a New York money manager and frequent critic of Citigroup’s current management and board. “He has overseen the entire meltdown, yet been compensated as an operating employee while bragging about having no operating responsibility.” Mr. Rubin can’t “have it both ways,” Mr. Smith added.

Somehow, the most central factor — the fundamental cause — of both the late-90s Asian meltdown and our current crisis — namely monetary and dollar policy — has escaped much criticism. Yes, the argument that Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke held interest rates too low for too long in the 2003-06 period can now be discussed in polite company. But it often is thought to be peripheral, or more often it just gets lost in all the chaos.

The late-90s mistake was just the opposite of this decade’s easy-credit mistake, with predictable mirror image effects. Back then, Greenspan and Rubin held a super-tight squeeze on dollars, pushing the dollar ever higher versus foreign currencies and commodities, crushing all dollar-debtors across the globe, from Thailand, Indonesia, and Korea, to Turkey, Russia, and Argentina. The world’s capital abandoned hard assets and flooded into the U.S. in general and into our soft, intellectual assets like Microsoft, Cisco, and dot-coms in particular. Eventually, after the “Committee to Save the World” had worked its magic and basked in its cover-boy status, the deflationary Greenspan/Rubin policy in 2000 toppled the U.S. markets, too.

Mr. Rubin likes to offer his wisdom “in an uncertain world” — the title of his memoir. But the world would be much less uncertain if the Rubin-Greenspan-Bernanke-Snow-Paulson monetary/dollar policy weren’t so manic.

P.S. Yes, to reiterate, these are supreme cases of the arsonist posing as heroic fireman.

Quote of the Day

“It is these periods of transition, where the value of the currency is changing fast, but before price changes filter through all commerce and contracts, when financial and political disruptions often take place.”

We’re all in this together

Zachary Karabell writes about China’s ever growing importance, especially now, with our stumbles and its $2 trillion in reserves.

China’s actions could also have direct — and positive — effects on the U.S. economy. An investment arm of the Chinese government is now deep in talks to buy up parts of AIG. China is already the primary source of growth for many U.S. companies, including ones like Caterpillar that make things in the U.S. and export them to China. As the developed world sags, China is becoming even more important to the global system.

China also needs a vibrant U.S. (and Europe). Beijing will likely take action to prevent a collapse by continuing to purchase U.S. Treasuries. We may not like the fact that China is our creditor, but having no creditor would be a good deal worse.

Even more important than its reserves, though, are the deeper sources of its economic strength — its decentralized entrepreneurial economy.

Update: In his final international address, President Bush pushed continued free trade with China. Good for him. But if only his administration had realized that its weak-dollar policy was effective protectionism, which boomeranged — as it always does. The policy inflated the home, oil, and credit bubbles, which of course led to our present crash.

“Buy property”

Really? That seems like an odd thing to advise at a time like this. But read David Dreman’s argument:

One last investment that should work out well over time: Buy property, if you live in a place with a forest of for-sale signs. The housing crisis is terrible, but it won’t last forever. If you can get a mortgage, and if I’m right about inflation, you will eventually be paying it back with 50- or 60-cent dollars. Pay 20% down on a house that rises 40% in five years and you’ll triple your investment, assuming you can cover the interest and maintenance with rental income. If prices rise above the rate of inflation, a reasonable possibility given how depressed they are now, your return will be still higher, possibly significantly so.

William Baldwin of Forbes comments:

Shrewd advice from an accomplished money man. But, at the same time, it’s dispiriting that he’s right. The way to make money is not by financing progress but by speculating against the ability of the Federal Reserve to do its job.

Gambling by investors is a good thing, if by that we mean gambling on the next Orville Wright or Steve Jobs. But the gamble against the dollar is something different. It’s one in which your windfall profit is matched by a windfall loss for the fellow on the other side of the table–the unfortunate saver who lent you the money for the house.

The Panic of ’08: Or, How a Jamaican Nanny Ended Up With Five Homes

Whether the topic is football or finance, Michael Lewis is maybe the best non-fiction story teller of our times. Now this author of Liar’s Poker, the smart-ass inside tale of Eighties Wall Street excess, finds the man who helped expose today’s housing charade and learns about real excess — the ’80s, how quaint — as he chronicles the 2008 crash.

More generally, the subprime market tapped a tranche of the American public that did not typically have anything to do with Wall Street. Lenders were making loans to people who, based on their credit ratings, were less creditworthy than 71 percent of the population. Eisman knew some of these people. One day, his housekeeper, a South American woman, told him that she was planning to buy a townhouse in Queens. “The price was absurd, and they were giving her a low-down-payment option-ARM,” says Eisman, who talked her into taking out a conventional fixed-rate mortgage. Next, the baby nurse he’d hired back in 1997 to take care of his newborn twin daughters phoned him. “She was this lovely woman from Jamaica,” he says. “One day she calls me and says she and her sister own five townhouses in Queens. I said, ‘How did that happen?’ ” It happened because after they bought the first one and its value rose, the lenders came and suggested they refinance and take out $250,000, which they used to buy another one. Then the price of that one rose too, and they repeated the experiment. “By the time they were done,” Eisman says, “they owned five of them, the market was falling, and they couldn’t make any of the payments.”

But the sub-prime detective Eisman still had not fully grasped the enormity and breadth of the problem.

That’s when Eisman finally got it. Here he’d been making these side bets with Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank on the fate of the BBB tranche without fully understanding why those firms were so eager to make the bets. Now he saw. There weren’t enough Americans with shitty credit taking out loans to satisfy investors’ appetite for the end product. The firms used Eisman’s bet to synthesize more of them. Here, then, was the difference between fantasy finance and fantasy football: When a fantasy player drafts Peyton Manning, he doesn’t create a second Peyton Manning to inflate the league’s stats. But when Eisman bought a credit-default swap, he enabled Deutsche Bank to create another bond identical in every respect but one to the original. The only difference was that there was no actual homebuyer or borrower.

Finally, Lewis lunches with his long-ago boss John Gutfreund, the Salomon Brothers CEO who he skewered almost 30 years ago.

[Gutfreund] thought the cause of the financial crisis was “simple. Greed on both sides—greed of investors and the greed of the bankers.” I thought it was more complicated. Greed on Wall Street was a given—almost an obligation. The problem was the system of incentives that channeled the greed.

Indeed, greed is ever-present. And not just on Wall Street. It is the incentives and discipline — the structure — of the market that keeps greed from pushing us over the cliff. It is this discipline of the market that makes service to others, in the words of George Gilder, more valuable than self-centered avarice. Had he taken it one step further, Lewis might have said that the ultimate disciplinarian — the taskmaster that demands real value instead of greed, froth, and fraud — is a rock-solid dollar.

Bubbleology

The prolific Niall Ferguson with a long narrative of the financial crash in Vanity Fair:

The key point is that without easy credit creation a true bubble cannot occur. That is why so many bubbles have their origins in the sins of omission and commission of central banks.

As I Was Just Saying…

On the eve of the G20 global financial summit, Judy Shelton weighs in with yet another brilliant exposition on stable money:

At the bottom of the world financial crisis is international monetary disorder. Ever since the post-World War II Bretton Woods system — anchored by a gold-convertible dollar — ended in August 1971, the cause of free trade has been compromised by sovereign monetary-policy indulgence.

Today, a soupy mix of currencies sloshes investment capital around the world, channeling it into stagnant pools while productive endeavor is left high and dry. Entrepreneurs in countries with overvalued currencies are unable to attract the foreign investment that should logically flow in their direction, while scam artists in countries with undervalued currencies lure global financial resources into brackish puddles.

Pearls of Unwisdom

Steve Pearlstein of the Washington Post is on Charlie Rose right now saying the U.S. trade deficit was a chief cause of the present financial crisis. He’s got it just backwards. It was our overreaction to the innocuous trade deficit — namely, inflationary weak-dollar easy credit, designed in part to close the trade gap — that brought us here. The weak-dollar Fed juiced oil and home prices. High oil prices boosted the trade deficit — just the opposite of the weak-dollar advocates‘ intent. Skyrocketing home prices required, and were fueled by, hyper-aggressive and unsustainable mortgage lending.

Pearlstein then said we needed an international regulator to stop this from happening. This entity should have stopped the U.S. from buying so much from China. Wrong again. We needed the Fed and Treasury to maintain a stable dollar. A stable currency is the ultimate financial regulator and disciplinarian. If we had ignored the trade deficit and focused on stable money, there would be no financial crisis.

Dr. Doom Persists

Chief panic prophet Nouriel Roubini sees long-term decline:

The U.S. will experience its most severe recession since World War II, much worse and longer and deeper than even the 1974-1975 and 1980-1982 recessions.

There’s no hope of a V-shaped recovery:

a U-shaped 18- to 24-month recession is now a certainty, and the probability of a worse, multi-year L-shaped recession (as in Japan in the 1990s) is still small but rising.

And there’s a real

risk that we will end in a deflationary liquidity trap as the Fed is fast approaching the zero-bound constraint for the Fed funds rate

leading to global

stag-deflation

When a permabear like Roubini has been right so often for the past year (lo for the wrong reasons) it may seem a tall order to refute him. But John Tamny does an admirable job:

just as housing was the hot asset class in the early and late ‘70s, so was it this decade not due to economic growth per se, but thanks to currency debasement that always leads to a flight to the real. In short, the subsequent moderation of home prices has not been an economic retardant so much as it’s been the result of economic sluggishness that always reveals itself when currencies are allowed to weaken.

Roubini holds the reputation of soothsayer at present, but the very analysis that has made him all-seeing was faulty on its face. Lower home prices are an undeniable good for less capital going into the ground, as opposed to the entrepreneurial economy. What led to housing’s moderation of late was paradoxically what caused its boom. When currencies decline, hard assets do well, and investment in real economic activity withers. . . .

In short, Roubini made the correct call a few years ago about looming economic difficulty, but the call ignored the real cause which decidedly was the weak dollar. Happily for Washington’s political class, Roubini’s suggestions for “stimulating” the economy absolve it of its own mistakes, all the while allowing it to do what it does best: spend the money of others.

2012?

Is Paul Ryan the future?

After two straight electoral defeats, it is time for a substantial party shake-up. We don’t need a feather duster; we need a fire hose.

We need to be honest about the root causes of our current financial crisis: loose money, crony capitalism and a lack of market transparency and information.

Obama’s Entrepreneurial Lesson

From my article in Friday’s Wall Street Journal:

If Barack Obama ran for president by calling for a heavier hand of government, he also won by running one of the most entrepreneurial campaigns in history.

Will he now grasp the lesson his campaign offers as he crafts policies aimed at reigniting the national economy? Amid a recession, two wars, and a global financial crisis, will he come to see that unleashing the entrepreneur is the best way to raise the revenue he needs for his lofty priorities?

Read the whole op-ed here, and listen to a brief radio interview here.

Whither Free Trade

John Tamny at Real Clear Markets on the roots and prospects for free trade:

In his Tract on Monetary Reform, John Maynard Keynes made the essential point that when money is debased, enterprise is discredited, and trade barriers soon reveal themselves. Having witnessed the worldwide monetary errors of the ‘20s that led to economic isolationism in the ‘30s, Keynes knew well the importance of the 1944 Bretton Woods monetary standard, of which he was a chief architect. . . .

Unfortunately, we’ve regressed. The chaotic monetary and currency policy of the present Administration has given rise to the trade skeptics of the next.

Tuesday’s “election could put trade-liberalization on ice for a while.”