Net neutrality activists have deployed a long series of rationales in their quest for government control of the Internet. As each rationale is found wanting, they simply move onto the next, more exotic theory. The debate has gone on so long that they’ve even begun recycling through old theories that were discredited long ago.

In the beginning, the activists argued that there should be no pay for performance anywhere on the Net. We pointed out the most obvious example of a harmful consequence of their proposal: their rules, as originally written, would have banned widely used content delivery networks (CDNs), which speed delivery of packets (for a price).

Then they argued that without strong government rules, broadband service providers would block innovation at the “edges” of the network. But for the last decade, under minimal regulation, we’ve enjoyed an explosion of new technologies, products, and services from content and app firms like YouTube, Facebook, Netflix, Amazon, Twitter, WhatsApp, Etsy, Snapchat, Pinterest, Twitch, and a thousand others. Many of these firms have built businesses worth billions of dollars.

They said we needed new rules because the light-touch regulatory environment had left broadband in the U.S. lagging its international rivals, whose farsighted industrial policies had catapulted them far ahead of America. Oops. Turns out, the U.S. leads the world in broadband. (See my colleague Richard Bennett’s detailed report on global broadband and my own.)

Then they argued that, regardless of how well the U.S. is doing, do you really trust a monopoly to serve consumer needs? We need to stop the broadband monopolist — the cable company. Turns out most Americans have several choices in broadband providers, and the list of options is growing — see FiOS, U-verse, Google Fiber, satellite, broadband wireless from multiple carriers, etc. No, broadband service is not like peanut butter. Because of the massive investments required to build networks, there will never be many dozens of wires running to each home. But neither is broadband a monopoly.

Artificially narrowing the market is the first refuge of nearly all bureaucrats concerned with competition. It’s an easy way to conjure a monopoly in almost any circumstance. My favorite example was the Federal Trade Commission’s initial opposition in 2003 to the merger of Haagen-Dasz (Nestle) and Godiva (Dreyer’s). The government argued it would harmfully reduce competition in the market for “super premium ice cream.” The relevant market, in the agency’s telling, wasn’t food, or desserts, or sweets, or ice cream, or even premium ice cream, but super premium ice cream.

Reports suggest the FCC is about to apply this narrowing trick: Chairman Tom Wheeler apparently wants to redefine “broadband” as a minimum data rate of 25 megabits per second downstream, up from the current 4 Mbps. Broadband providers with speeds of 24.9 Mbps would be defined out of the market. Voilà. A market in which most Americans have several options — and a growing number and variety of options — suddenly becomes a “monopoly.”

But this redefinition of broadband, without any substance or research or deliberation by the Commission, is so arbitrary and capricious, it will never stand up in court.

So they have a back-up argument. And this one’s a real doozy. Perhaps there are several broadband competitors, the new theory goes, but each of those broadband competitors is a monopolist. Specifically, they say, each broadband provider enjoys a “terminating access monopoly” — a monopoly in the market of its own customers. It’s the WD-40 of regulation — an all-purpose justification for any regulation, anytime, in any market. It’s the ultimate narrowing trick, a bureaucrat’s dream.

If I can define a market as the relationship between one supplier and one consumer, I can label anything a monopoly.

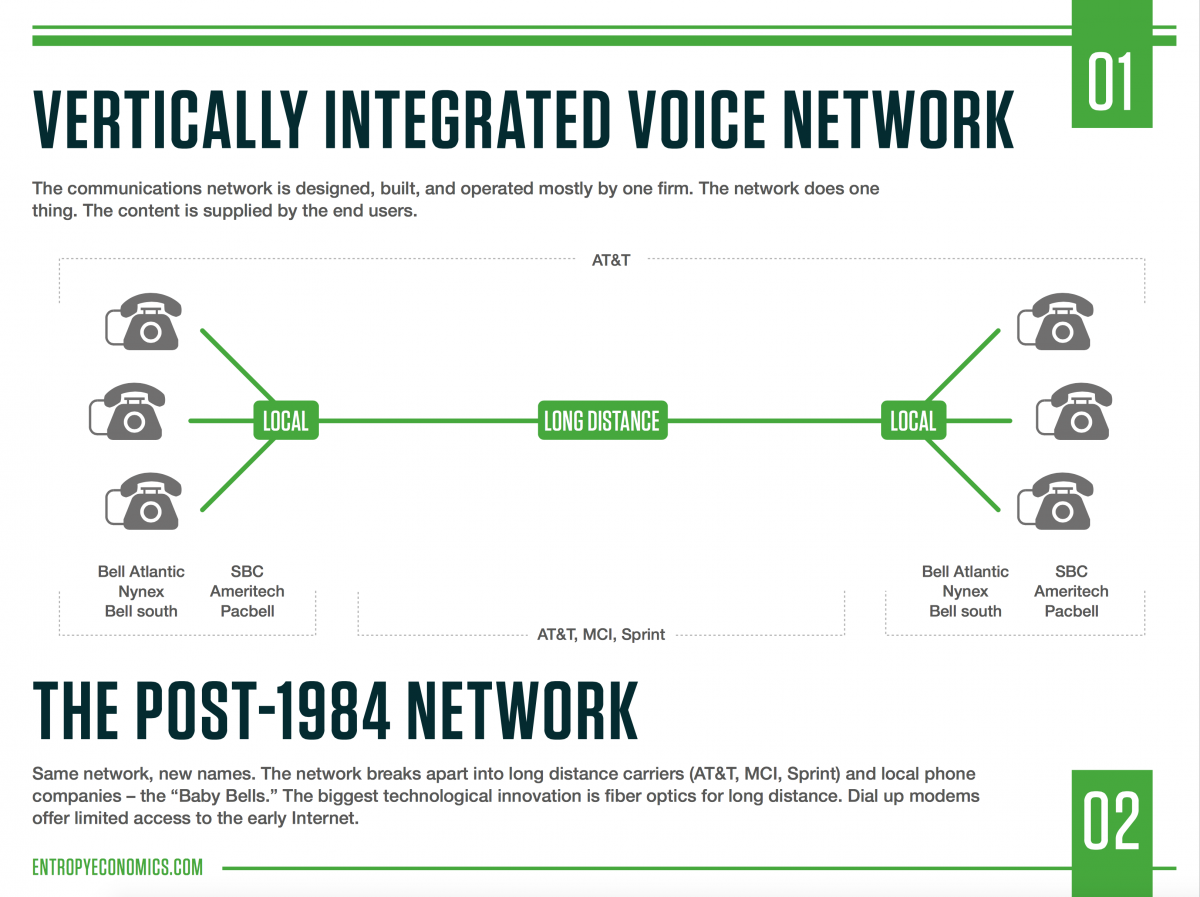

Terminating access monopoly is a term and concept from the old telephone network, when actual telephone monopolies, or Local Exchange Carriers (LECs), provided the only connections available. Long distance carriers, or interexchange carriers (IXCs), had to go through the LECs to reach customers at each end of the line. The LECs thus were said to enjoy a terminating access monopoly on the “called party.”

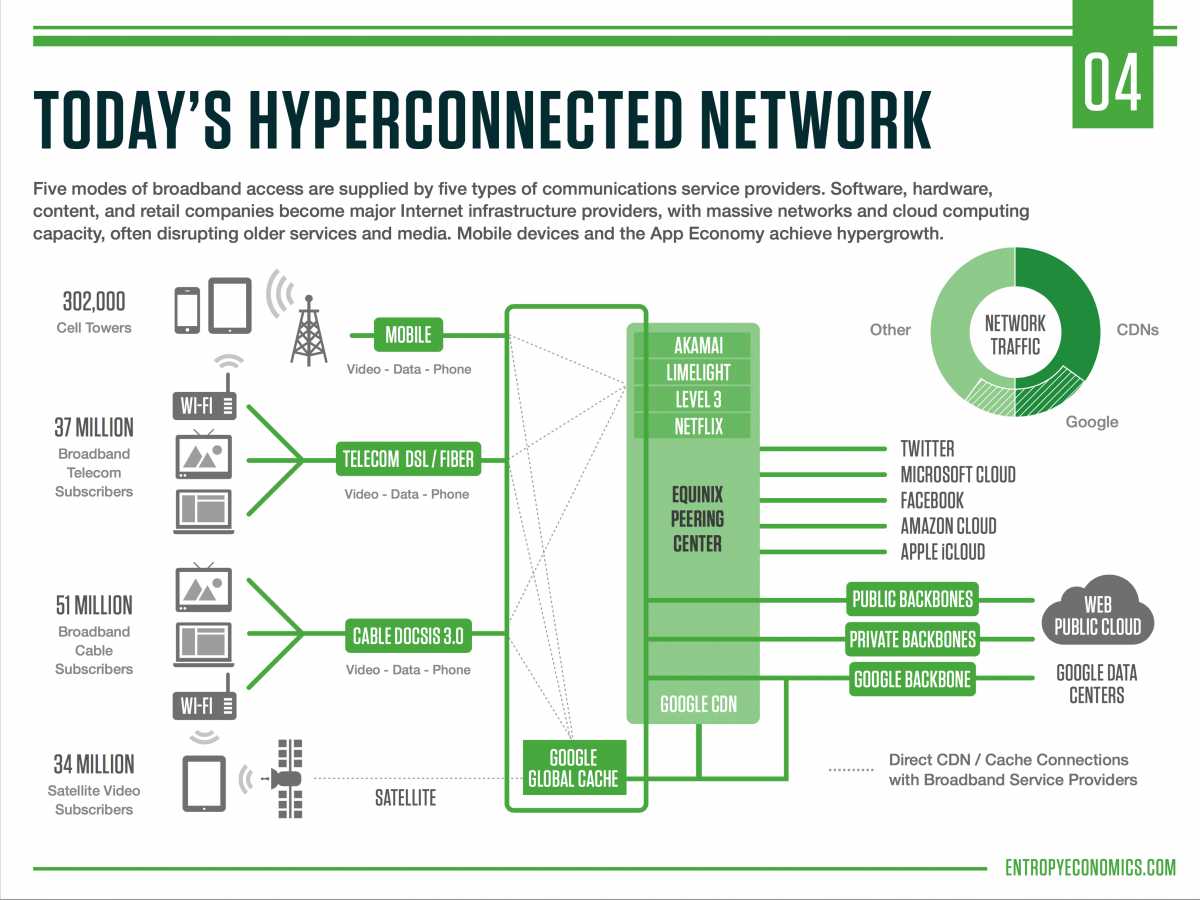

The market structure, technology, and regulations of the old telephone network, however, are very different from today’s Internet. In the diagrams below, see how simple the old communications network was in contrast with the complexity of today’s Internet. (For the full set of diagrams and the accompanying report, see “Hyperconnected: The New Network Map” and “Digital Dynamism: Competition in the Internet Ecosystem.”) In the old days, one network, divided up essentially between local and long distance, supplied one type of service. Today, multiple networks, service providers, and content providers connect to and interact with one another and supply a wide variety of products and services to highly diverse consumers and end-point devices.

A new paper by economists Andres Lerner and Janusz Ordover surveys the history of the terminating access monopoly theory and examines whether it applies in modern communications. They find it does not. And they show that any suggestion of a TAM in the wireless market is especially ridiculous.

Among the many reasons the terminating access monopoly concept no longer applies, Lerner and Ordover show that:

- in the old telephone market, the long distance IXC had no relationship with the terminating LEC’s customers, or the “called party.” Thus a monopoly LEC could theoretically impose high termination fees on the IXC, and the IXC would have no recourse in the market. In today’s market, online content providers are highly differentiated and often have direct relationships with consumers.

- 93 percent of Americans have access to two nationwide providers of 4G LTE broadband wireless service, and 91 percent have access to four or more wireless providers. “Churn” in the industry is constant and is a phenomenon that providers try desperately to reduce. Blocking content or charging exorbitant fees on content providers (which could be circulated back to consumers) would cause reactions by consumers — switching providers or reducing usage — in a “feedback loop” that did not exist on the telephone network.

- “consumers generally ‘multi-home’ by accessing online content and services on multiple platforms, such as one or more wireless broadband services, a wireline broadband service at home, a wireline broadband service at work, and Wi-Fi networks at numerous locations (e.g., Starbucks, libraries, airports).”

On the telephone network, a called party would not know which long distance carrier carried the phone call, nor notice if the LEC was charging the IXC excessive fees. Online, the consumer has a relationship with, for example, Gmail, Netflix, Facebook, and Skype. The number and variety of content providers is unlike the old long distance transmission service, which was a kind of nameless, faceless commodity. The number and variety of connectivity options is unlike the old telephone system, in which one network supplied one service. The economic relationships among today’s broadband providers, content providers, and consumers are more varied, flexible, and responsive to market forces.

In fact, today’s Internet ecosphere is so complex and dynamic that it is difficult to grasp the large number of both competitive and complementary forces at play. Below, however, is a partial list of these forces, which shows just how far away from the telephone world we are.

Nothing like this set of constantly changing competitive and complementary technologies, firms, and economic forces existed in the terminating access monopoly days. The TAM was a creature of limited technology and a government enforced monopoly under Title II of the Communications Act. Title II regulation of the Internet would likely create new terminating access monopolies, where none exist today.

Nothing like this set of constantly changing competitive and complementary technologies, firms, and economic forces existed in the terminating access monopoly days. The TAM was a creature of limited technology and a government enforced monopoly under Title II of the Communications Act. Title II regulation of the Internet would likely create new terminating access monopolies, where none exist today.