On Wednesday, a House Judiciary subcommittee heard testimony on the potential for existing general-purpose antitrust, competition, and consumer protection laws to police the Internet. Until the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) issued its 2015 Title II Order, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) oversaw these functions. The 2015 rule upended decades worth of successful policy, but now that the new FCC is likely to return the Internet to its original status as a Title I information service, Title II advocates are warning that general purpose law and the FTC are not equipped to deal with the Internet. They’re also hoping that individual states enter the Internet regulation game. I think they are wrong on both counts.

In fact, it’s more important than ever that we govern the sprawling Internet with general purpose laws and economic principles, not the outdated, narrow, vertical silos of a 1934 monopoly telephone law. And certainly not a patchwork of conflicting state laws. The Internet is not just “modernized telephone wires.” It is a broad and deep ecosystem of communications and computing infrastructure; vast, nested layers of software, applications, and content; and increasingly varied services connecting increasingly diverse end-points and industries. General purpose rules are far better suited to this environment than the 80-year old law written to govern one network, built and operated by one company, to deliver one service.

Over the previous two decades of successful operation under Title I, telecom, cable, and mobile firms in the U.S. invested a total of $1.5 trillion in wired and wireless broadband networks. But over the last two years, since the Title II Order, the rate of investment has slowed. In 2014, the year before the Title II Order, U.S. broadband investment was $78.4 billion, but in 2016 that number had dropped by around 3%, to $76 billion. In the past, annual broadband investment had only dropped during recessions.

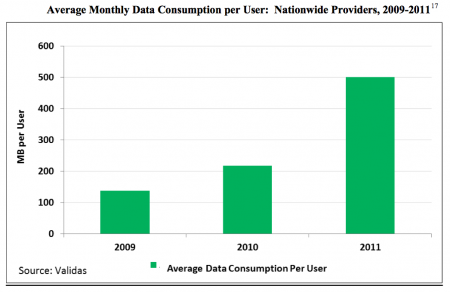

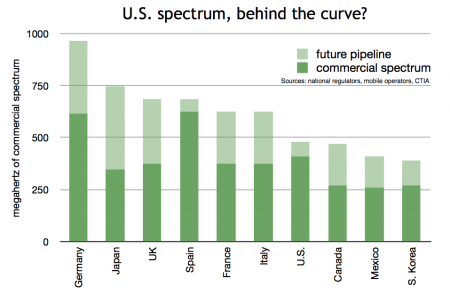

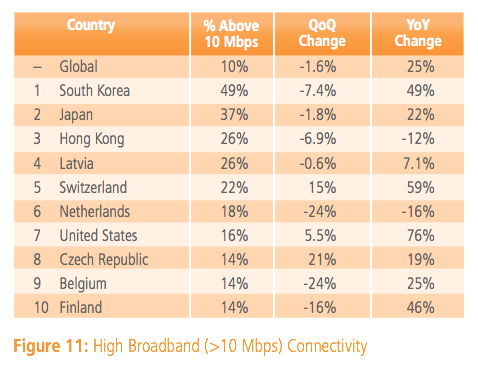

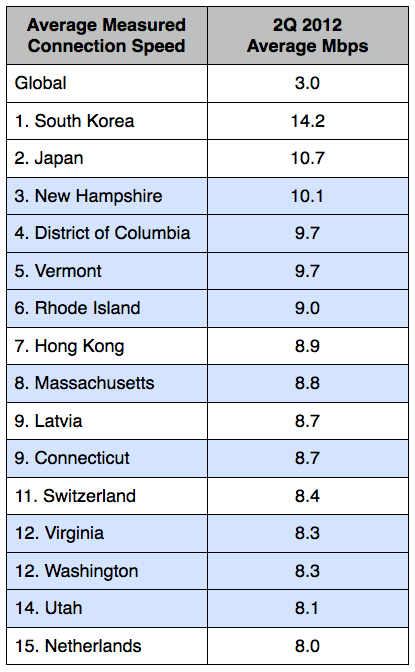

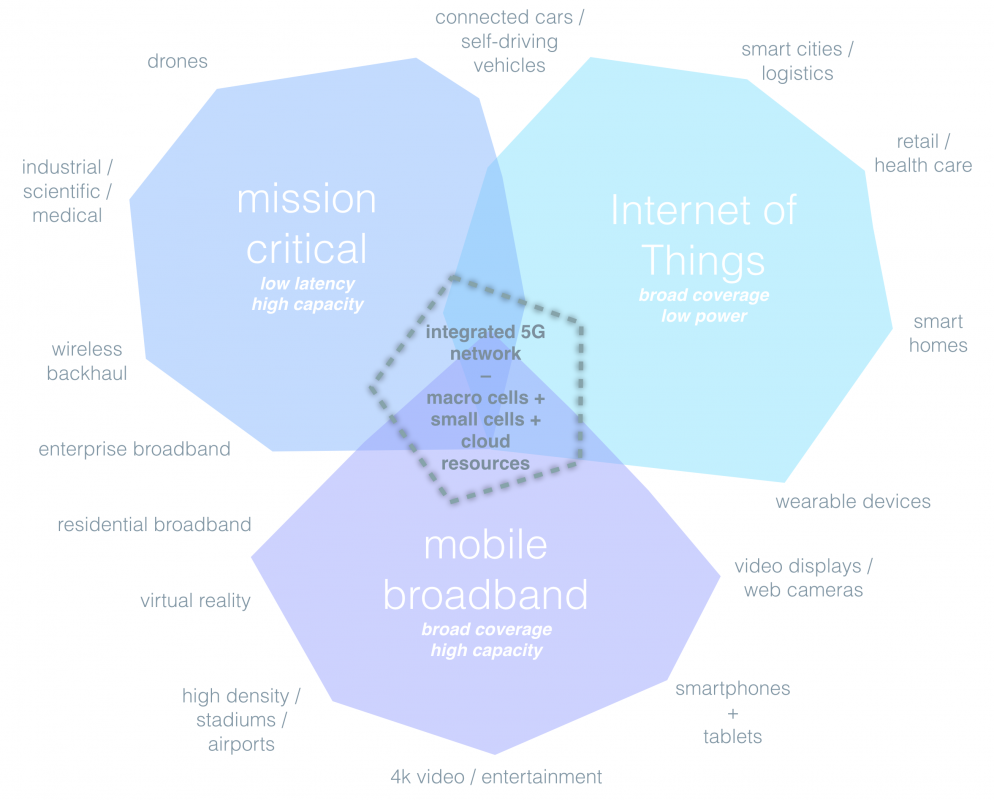

This is a concern because massive new investments are needed to fuel the next waves of Internet innovation. If we want to quickly and fully deploy new 5G wireless networks over the coming 15 years, for example, we need to extend fiber optic networks deeper into neighborhoods and more broadly across the nation in order to connect millions of new “small cells” that will not only deliver ever more video to our smartphones but also enable autonomous vehicles and the Internet of Things. It’s a project that may cost $250-300 billion, but it would happen far more slowly under Title II, and many marginal investments in marginal geographies might never happen at all.

At the hearing, FTC Commissioner Terrell McSweeny defended the 2015 Title II order, which poached many oversight functions from her own agency. Her reasoning was odd, however. She said that we needed to radically change policy in order to preserve the healthy results of previously successful policy. She said the Internet’s success depended on its openness, and we could sustain that openness only by applying the old telephone regulations, for the first time, to the Internet.

This gets things backwards. In our system, we usually intervene in markets and industries only if we demonstrate both serious and widespread market failures and if we think a policy can deliver clear improvements compared to its possible downside. In other words, the burden is on the government to prove harm and that it can better manage an industry. The demonstrable success of the Internet made this a tough task for the FCC. In the end, the FCC didn’t perform a market analysis, didn’t show market failures or consumer harm, didn’t show market power, and didn’t perform a cost-benefit analysis of its aggressive new policy. It simply asserted that it knew better how to manage the technology and business of the Internet, compared to engineers and entrepreneurs who had already created one of history’s biggest economic and technical successes.

Commissioner McSweeny also disavowed what had been one of the FTC’s most important new-economy functions and one in which it had developed a good bit of expertise – digital privacy. Under the Title II Order, the FCC snatched from the FTC the power to regulate Internet service providers (ISPs) on matters of digital privacy. Now that the FCC looks to be returning that power to the FTC, however, some states are attempting to regulate Internet privacy themselves. This summer, for example, California legislators tried to impose the Title II Order’s privacy rules on ISPs. Although that bill didn’t pass, you can bet California and other states will be back.

It’s important, therefore, that the FCC reaffirm longstanding U.S. policy – that the Internet is the ultimate form of interstate commerce. Here’s the way we put it in a recent post:

The internet blew apart the old ways of doing things. Internet access and applications are inherently nonlocal services. In this sense, the “cloud” analogy is useful. Telephones used to be registered to a physical street address. Today’s mobile devices go everywhere. Data, services, and apps are hosted in the cloud at multiple locations and serve end users who could be anywhere — likewise for peer-to-peer applications, which connect individual users who are mobile. Along most parameters, it makes no sense to govern the internet locally. Can you imagine 50 different laws governing digital privacy or net neutrality? It would be confusing at best, but more likely debilitating.

The Democratic FCC Chairman Bill Kennard weighed in on this matter in the late 1990s. He was in the middle of the original debate over broadband and argued firmly that high-speed cable modems were subject to a national policy of “unregulation” and should not be swept into the morass of legacy regulation.

In a 1999 speech, he admonished those who would seek to regulate broadband at the local or state level:

“Unfortunately, a number of local franchising authorities have decided not to follow this de-regulatory, pro-competitive approach. Instead, they have begun imposing their own local open access provisions. As I’ve said before, it is in the national interest that we have a national broadband policy. The FCC has the authority to set one, and we have. We have taken a de-regulatory approach, an approach that will let this nascent industry flourish. Disturbed by the effect that the actions of local franchising authorities could have on this policy and on the deployment of broadband, I have asked our general counsel to prepare a brief to be filed in the pending Ninth Circuit case so we can explain to the court why it’s important that we have a national policy.”

In the coming months, the FCC will likely reclassify the internet as a Title I information service. In addition to freeing broadband and mobile from the regulatory straitjacket of the 2015 Title II Order, this will also return oversight responsibility for digital privacy to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), its natural home. The FTC has spent the last decade developing rules governing this important and growing arena and has enforced those rules to protect consumers. States’ efforts to impose their own layer of possibly contradictory rules would only confuse consumers and discourage upstart innovators.

As the internet becomes an ever more important component of all that we do, as its complexity spreads, and as it touches more parts of the economy, this principle will only become more important. Yes, there will be legitimate debates over just where to draw the boundaries. As the internet seeps further into every economic and social act, this does not mean that states will lose all power to govern. But to the extent that Congress, the FCC, and the FTC have the authority to protect the free flow of internet activity against state-based obstacles and fragmentation, they should do so. In its coming order, the FCC should reaffirm the interstate nature of these services.

A return to the Internet’s original status as a Title I information service, protected from state-based fragmentation, merely extends and strengthens the foundation upon which the U.S. invented and built the modern information economy.

“A revival of economic growth in the U.S. and around the world will, to a not insignificant degree, depend on the successful deployment of the next generation of wireless technology.

“A revival of economic growth in the U.S. and around the world will, to a not insignificant degree, depend on the successful deployment of the next generation of wireless technology.