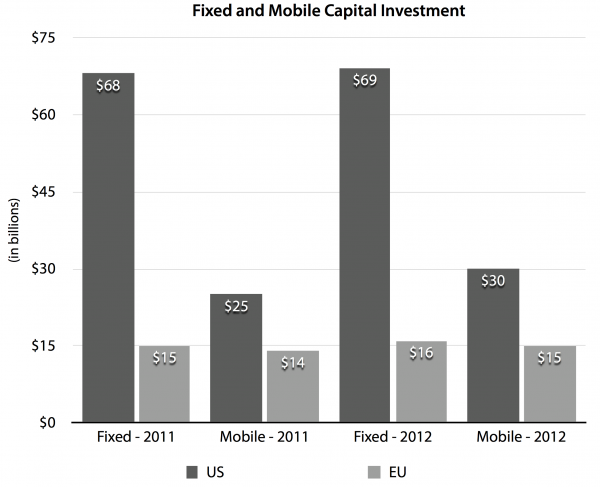

In its effort to regulate the Internet, the Federal Communications Commission is swimming upstream against a flood of evidence. The latest data comes from Fred Campbell and the Internet Innovation Alliance, showing the startling disparities between the mostly unregulated and booming U.S. broadband market, and the more heavily regulated and far less innovative European market. In November, we showed this gap using the measure of Internet traffic. Here, Campbell compares levels of investment and competitive choice (see chart below). The bottom line is that the U.S. invests around four times as much in its wired broadband networks and about twice as much in wireless. It’s not even close. Why would the U.S. want to drop America’s hugely successful model in favor of “President Obama’s plan to regulate the Internet,” which is even more restrictive and intrusive than Europe’s?

A Decade Later, Net Neutrality Goes To Court

Today the D.C. Federal Appeals Court hears Verizon’s challenge to the Federal Communications Commission’s “Open Internet Order” — better known as “net neutrality.”

Hard to believe, but we’ve been arguing over net neutrality for a decade. I just pulled up some testimony George Gilder and I prepared for a Senate Commerce Committee hearing in April 2004. In it, we asserted that a newish “horizontal layers” regulatory proposal, then circulating among comm-law policy wonks, would become the next big tech policy battlefield. Horizontal layers became net neutrality, the Bush FCC adopted the non-binding Four Principles of an open Internet in 2005, the Obama FCC pushed through actual regulations in 2010, and now today’s court challenge, which argues that the FCC has no authority to regulate the Internet and that, in fact, Congress told the FCC not to regulate the Internet.

Over the years we’ve followed the debate, and often weighed in. Here’s a sampling of our articles, reports, reply comments, and even some doggerel:

- “CBS-Time Warner Cable Spat Shows (Once Again) Why ‘Net Neutrality’ Won’t Work” – by Bret Swanson – August 9, 2013

- “Verizon, ESPN, and the Future of Broadband” – by Bret Swanson – Forbes.com – June 4, 2013

- “The Internet Survives, and Thrives, For Now” – by Bret Swanson – RealClearMarkets – December 6, 2010

- “Reply Comments to the FCC’s Open Internet Further Inquiry” – by Bret Swanson – November 4, 2010

- “Net Neutrality, Investment, and Jobs: Assessing the Potential Impact on the Broadband Ecosystem” – by Charles M. Davidson and Bret T. Swanson, Advanced Communications Law and Policy Institute, New York Law School, June 16, 2010

- “The Regulatory Threat to Web Video” – by Bret Swanson – Forbes.com – May 17, 2010

- “Reply Comments in the FCC Matter of ‘Preserving the Open Internet’” – by Bret Swanson – April 26, 2010

- “What Would Net Neutrality Mean for U.S. Jobs?” – by Bret Swanson – February 5, 2010

- “Net Neutrality’s Impact on Internet Innovation” – prepared for the New York City Council – by Bret Swanson – November 20, 2009

- “Google and the Problem With ‘Net Neutrality’” – by Bret Swanson, The Wall Street Journal, October 5, 2009

- “Leviathan Spam” – by Bret Swanson – A whimsical take on “Net Neutrality” – September 23, 2009

- “Unleashing the ‘Exaflood’” – by Bret Swanson and George Gilder, The Wall Street Journal, February 22, 2008

- “The Coming Exaflood” – by Bret Swanson, The Wall Street Journal, January 20, 2007

- “Let There Be Bandwidth” – by Bret Swanson, The Wall Street Journal, March 7, 2006

- “Testimony For Telecommunications Policy: A Look Ahead” – testimony before the Senate Commerce Committee – by George Gilder – April 28, 2004

— Bret Swanson

Quote of the Day

The statute wants a competitive analysis, but as the Commission correctly points out, competition is not the goal, it the means. Better performance is the goal. When the evidence presented in the Sixteenth Report is viewed in this way, the conclusion to be reached about the mobile industry, at least to me, is obvious: the U.S. mobile wireless industry is performing exceptionally well for consumers, regardless of whether or not it satisfies someone’s arbitrarily-defined standard of “effective competition.”

— George Ford, Phoenix Center chief economist, commenting on the FCC’s 16th Wireless Competition report.

The Broadband Rooster

FCC chairman Julius Genachowski opens a new op-ed with a bang:

As Washington continues to wrangle over raising revenue and cutting spending, let’s not forget a crucial third element for reining in the deficit: economic growth. To sustain long-term economic health, America needs growth engines, areas of the economy that hold real promise of major expansion. Few sectors have more job-creating innovation potential than broadband, particularly mobile broadband.

Private-sector innovation in mobile broadband has been extraordinary. But maintaining the creative momentum in wireless networks, devices and apps will need an equally innovative wireless policy, or jobs and growth will be left on the table.

Economic growth is indeed the crucial missing link to employment, opportunity, and healthier government budgets. Technology is the key driver of long term growth, and even during the downturn the broadband economy has delivered. Michael Mandel estimates the “app economy,” for example, has created more than 500,000 jobs in less than five short years of existence.

We emphatically do need policies that will facilitate the next wave of digital innovation and growth. Chairman Genachowski’s top line assessment — that U.S. broadband is a success — is important. It rebuts the many false but persistent claims that U.S. broadband lags the world. Chairman Genachowski’s diagnosis of how we got here and his prescriptions for the future, however, are off the mark.

For example, he suggests U.S. mobile innovation is newer than it really is.

Over the past few years, after trailing Europe and Asia in mobile infrastructure and innovation, the U.S. has regained global leadership in mobile technology.

This American mobile resurgence did not take place in just the last “few years.” It began a little more than decade ago with smart decisions to:

(1) allow reasonable industry consolidation and relatively free spectrum allocation, after years of forced “competition,” which mandated network duplication and thus underinvestment in coverage and speed (we did in fact trail Europe in some important mobile metrics in the late 1990s and briefly into the 2000s);

(2) refrain from any but the most basic regulation of broadband in general and the mobile market in particular, encouraging experimental innovation; and

(3) finally implement the digital TV / 700 MHz transition in 2007, which put more of the best spectrum into the market.

These policies, among others, encouraged some $165 billion in mobile capital investment between 2001 and 2008 and launched a wave of mobile innovation. Development on the iPhone began in 2004, the iPhone itself arrived in 2007, and the app store in 2008. Google’s Android mobile OS came along in 2009, the year Mr. Genachowski arrived at the FCC. By this time, the American mobile juggernaut had already been in full flight for years, and the foundation was set — the U.S. topped the world in 3G mobile networks and device and software innovation. Wi-Fi, meanwhile surged from 2003 onward, creating an organic network of tens of millions of wireless nodes in homes, offices, and public spaces. Mr. Genachowski gets some points for not impeding the market as aggressively as some other more zealous regulators might have. But taking credit for America’s mobile miracle smacks of the rooster proudly puffing his chest at sunrise.

More important than who gets the credit, however, is determining what policies led to the current success . . . and which are likely to spur future growth. Chairman Genachowski is right to herald the incentive auctions that could unleash hundreds of megahertz of un- and under-used spectrum from the old TV broadcasters. Yet wrangling over the rules of the auctions could stretch on, delaying the the process. Worse, the rules themselves could restrict who can bid on or buy new spectrum, effectively allowing the FCC to favor certain firms, technologies, or friends at the expense of the best spectrum allocation. We’ve seen before that centrally planned spectrum allocations don’t work. The fact that the FCC is contemplating such an approach is worrisome. It runs counter to the policies that led to today’s mobile success.

The FCC also has a bad habit of changing the metrics and the rules in the middle of the game. For example, the FCC has been caught changing its “spectrum screen” to fit its needs. The screen attempts to show how much spectrum mobile operators hold in particular markets. During M&A reviews, however, the FCC has changed its screen procedures to make the data fit its opinion.

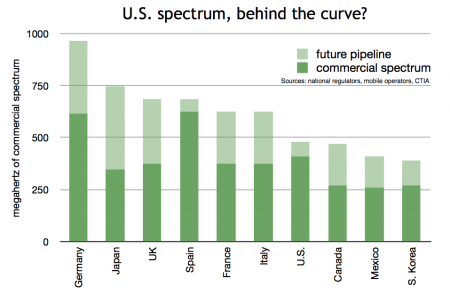

In a more recent example, Fred Campbell shows that the FCC alters its count of total available commercial spectrum to fit the argument it wants to make from day to day. We’ve shown that the U.S. trails other nations in the sum of currently available spectrum plus spectrum in the pipeline. Below, see a chart from last year showing how the U.S. compares favorably in existing commercially available spectrum but trails severely in pipeline spectrum. Translation: the U.S. did a pretty good job unleashing spectrum in 1990s through he mid-2000s. But, contrary to Chairman Genachowski’s implication, it has stalled in the last few years.

When the FCC wants to argue that particular companies shouldn’t be allowed to acquire more spectrum (whether through merger or secondary markets), it adopts this view that the U.S. trails in spectrum allocation. Yet when challenged on the more general point that the U.S. lags other nations, the FCC turns around and includes an extra 139 MHz in spectrum in the 2.5 GHz range to avoid the charge it’s fallen behind the curve.

Next, Chairman Genachowski heralds a new spectrum “sharing” policy where private companies would be allowed to access tiny portions of government-owned airwaves. This really is weak tea. The government, depending on how you measure, controls between 60% and 85% of the best spectrum for wireless broadband. It uses very little of it. Yet it refuses to part with meaningful portions, even though it would still be left with more than enough for its important uses — military and otherwise. If they can make it work (I’m skeptical), sharing may offer a marginal benefit. But it does not remotely fit the scale of the challenge.

Along the way, the FCC has been whittling away at mobile’s incentives for investment and its environment of experimentation. Chairman Genachowski, for example, imposed price controls on “data roaming,” even though it’s highly questionable he had the legal authority to do so. The Commission has also, with varied degrees of “success,” been attempting to impose its extralegal net neutrality framework to wireless. And of course the FCC has blocked, altered, and/or discouraged a number of important wireless mergers and secondary spectrum transactions.

Chairman Genachowski’s big picture is a pretty one: broadband innovation is key to economic growth. Look at the brush strokes, however, and there are reasons to believe sloppy and overanxious regulators are threatening to diminish America’s mobile masterpiece.

— Bret Swanson

The $66-billion Internet Expansion

Sixty-six billion dollars over the next three years. That’s AT&T’s new infrastructure plan, announced yesterday. It’s a bold commitment to extend fiber optics and 4G wireless to most of the country and thus dramatically expand the key platform for growth in the modern U.S. economy.

The company specifically will boost its capital investments by an additional $14 billion over previous estimates. This should enable coverage of 300 million Americans (around 97% of the population) with LTE wireless and 75% of AT&T’s residential service area with fast IP broadband. It’s adding 10,000 new cell towers, a thousand distributed antenna systems, and 40,000 “small cells” that augment and extend the wireless network to, for example, heavily trafficked public spaces. Also planned are fiber optic connections to an additional 1 million businesses.

As the company expands its fiber optic and wireless networks — to drive and accommodate the type of growth seen in the chart above — it will be retiring parts of its hundred-year-old copper telephone network. To do this, it will need cooperation from federal and state regulators. This is the end of phone network, the transition to all Internet, all the time, everywhere.

R.H. Stands for Regulatory Hubris

“It is the single worst telecom bill that I have ever seen.”

— Reed Hundt, Jan. 31, 2012

Isn’t this rich?

One of the most zealous regulators America has known says Congress is overstepping its bounds because it wants to unleash lots of new wireless spectrum but also wants to erect a few guardrails so that FCC regulators don’t run roughshod over the booming mobile broadband market.

At a New America Foundation event yesterday, former FCC chairman Reed Hundt said Congress shouldn’t micromanage the FCC’s ability to micromanage the wireless industry. Mr. Congressman, you don’t know anything about how the FCC should regulate the Internet. But the FCC does know how to build networks, run mobile Internet businesses, and perfectly structure a wildly tumultuous economic sector. It’s just the latest remarkable example of the growing hubris of the regulatory state.

In his book, You Say You Want a Revolution, Hundt famously recounted his staff’s interpretation and implementation of the 1996 Telecom Act.

The passage of the new law placed me on a far more public stage. But I felt Congress — in the constitutional sense — had asked me to exercise the full power of all ideas I could summon. And I believed that I and my team had learned, through many failures, how to succeed. Later, I realized that we knew almost nothing of the complexity and importance of the tasks in front of the FCC.

…

Meeting in several overlapping groups of about a dozen people each . . . we dedicated almost three weeks to studying the possible readings of each word in the 150-page statute. The conference committee compromises had produced a mountain of ambiguity that was generally tilted toward the local phone companies’ advantage. But under the principles of statutory interpretation, we had broad authority to exercise our discretion in writing the implementing regulations. Indeed, like the modern engineers trying to straighten the Leaning Tower of Pisa, we could aspire to provide the new entrants to the local telephone markets a fairer chance to compete than they might find in any explicit provision of the law. In addition, the law gave almost no guidance about how to treat the Internet, data networks, . . . and many other critical issues. (Three years later, Justice Antonin Scalia agreed, on behalf of the Supreme Court, that the law was profoundly ambiguous.)

…

The more my team studied the law, the more we realized our decisions could determine the winners and losers of the new economy. We did not want to confer advantage on particular companies; that seemed inequitable. But inevitably

wink, wink,

a decision that promoted entry into the local market would benefit a company that followed such a strategy.

There are so many angles here.

(1) Hundt says he and his team basically stretched the statute to mean whatever they wanted. The law may have been ambiguous — and it was, I’m not going to defend the ’96 Act — yet the Supreme Court still found in a series of early-2000s cases that Hundt’s FCC had wildly overstepped even these flimsy bounds. That’s how aggressive and unconstrained Hundt was.

(2) Hundt’s rules helped crash the tech and telecom sectors in 2000-2002. His rules were so complex and intrusive that, whatever your views about the CLEC wars, the PCS C block spectrum debacle, and other battles, it’s hard to deny that the paralysis caused by the rules hurt broadband and the nascent Net.

(3) Is it surprising that, given the FCC’s poor record of reaching way past its granted powers, some in Congress want to circumscribe FCC regulators by giving them less-than-omnipotent authority? Is the new view of elite regulators that Congress should pass laws, the full text of which might read: “§1. Congress grants to the Internet Agency the authority to regulate the Internet. Go forth and regulate.”

(4) On the other hand, it’s not clear why Hundt would care particularly what Congress says in any new spectrum statute. He didn’t care much for the words or intent of the ’96 Act, and he thinks regulators should “aspire” to grand self-appointed projects. Who knows, maybe all those Supreme Court smack downs in the early 2000s made an impression.

(5) Hundt says he and his team later realized, in effect, how naive they were about “the complexity and importance of the tasks in front of the FCC.” So he’s acknowledging after things didn’t go so well that his FCC underestimated the complexity and thus overestimated their own expertise . . . yet he says today’s FCC deserves comprehensive power to structure the mobile Internet as it sees fit?

(6) Hundt admitted his FCC relished its capacity to pick winners and losers. Not particular companies, mind you — that would be improper — merely the types of companies who win and lose. A distinction without very much of a difference.

(7) We don’t argue that Congress, instead of the FCC, should impose intrusive regulation through statute. We don’t advocate long and complex laws. That’s not the point. Laws should be clear and simple, but stating the boundaries of a regulator’s authority is not a controversial act. No one should be imposing intrusive regulation or overdetermining the structure of an industry. And that’s what Congress — perhaps in a rare case! — is protecting against here.

Roam, roam on the range. Will Washington’s new intrusions discourage wireless expansion?

The U.S. wireless sector has been only mildly regulated over the last decade. We’d argue this is a key reason for its success. But this presumption of mostly unfettered experimentation and dynamism may be changing.

Consider Sprint’s apparent decision to use “roaming” in Oklahoma and Kansas instead of building its own network. Now, roaming is a standard feature of mobile networks worldwide. Company A might not have as much capacity as it would like in some geography, so it pays company B, who does have capacity there, for access. Company A’s customers therefore get wider coverage, and Company B is paid for use of its network.

The problem comes with the FCC’s 2011 “digital roaming” order. Last spring three FCC commissioners decided that private mobile services — which the Communications Act says “shall not . . . be treated as a common carrier” — are a common carrier. Only D.C. lawyers smarter than you and me can figure out how to transfigure “shall not” into “may.” Anyway, the possible effect is to subject mobile data — one of the fastest growing sectors anywhere on earth — to all sorts of forced access mandates and price controls.

We warned here and here that turning competitive broadband infrastructure into a “common carrier” could discourage all players in the market from building more capacity and covering wider geographies. If company A can piggyback on company B’s network at below market rates, why would it build its own expensive network? And if company B’s network capacity is going to company A’s customers, instead of its own customers, do we think company B is likely to build yet more cell sites and purchase more spectrum?

With 37 million iPhones and 15million iPads sold last quarter, we need more spectrum, more cell towers, more capacity. This isn’t the way to get it. And what we are seeing with Sprint’s decision to roam instead of build in Oklahoma and Kansas may be the tip of this anti-investment iceberg.

Last spring when the data roaming order came down we began wondering about a possible “slow walk to a reregulated communications market.” Among other items, we cited net neutrality, possible new price controls for Special Access links to cell sites, and a host of proposed regulations affecting things like behavioral advertising and intellectual property (see, PIPA/SOPA). Since then we’ve seen the government block the AT&T-T-Mobile merger. And the FCC is now holding up its own important push for more wireless spectrum because it wants the right to micromanage who gets what spectrum and how mobile carriers can use it.

Many of these items can be thoughtfully debated. But the number of new encroachments onto the communications sector threatens to slow its growth. Many of these encroachments, moreover, are taking place outside any basic legislative authority. In the digital roaming and net neutrality cases, for example, the FCC appeared clearly to grant itself extra- if not il-legal authority. These new regulations are now being challenged in court.

We need some restraint across the board on these matters. The Internet is too important. We can’t allow a quiet, gradual reregulation of the sector to slow down our chief engine of economic growth.

— Bret Swanson

Up-is-down data roaming vote could mean mobile price controls

Section 332(c)(2) of the Communications Act says that “a private mobile service shall not . . . be treated as a common carrier for any purpose under this Act.”

So of course the Federal Communications Commission on Thursday declared mobile data roaming (which is a private mobile service) a common carrier. Got it? The law says “shall not.” Three FCC commissioners say, We know better.

This up-is-down determination could allow the FCC to impose price controls on the dynamic broadband mobile Internet industry. Up-is-down legal determinations for the FCC are nothing new. After a decade trying, I’ve still not been able to penetrate the legal realm where “shall not” means “may.” Clearly the FCC operates in some alternate jurisprudential universe.

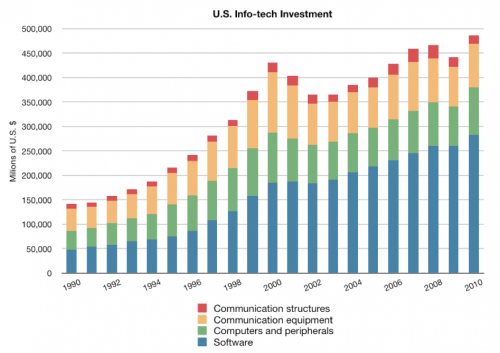

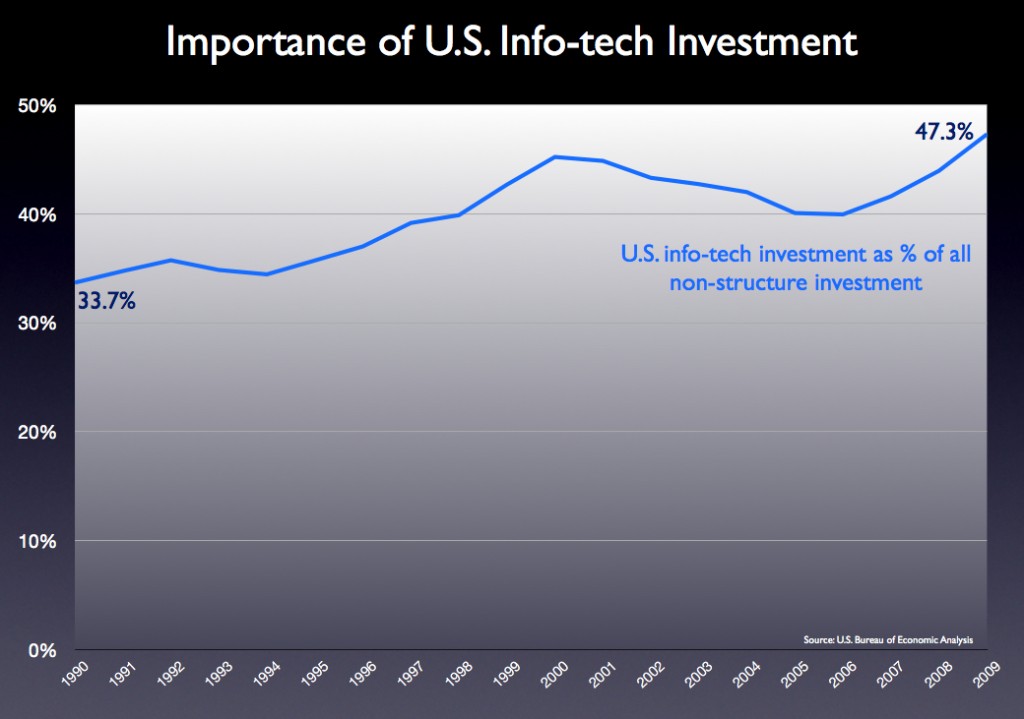

I do know the decision’s practical effect could be to slow mobile investment and innovation. It takes lots of money and know-how to build the Internet and beam real-time videos from anywhere in the world to an iPad as you sit on your comfy couch or a speeding train. Last year the U.S. invested $489 billion in info-tech, which made up 47% of all non-structure capital expenditures. Two decades ago, info-tech comprised just 33% of U.S. non-structure capital investment. This is a healthy, growing sector.

As I noted a couple weeks ago,

You remember that “roaming” is when service provider A pays provider B for access to B’s network so that A’s customers can get service when they are outside A’s service area, or where it has capacity constraints, or for redundancy. These roaming agreements are numerous and have always been privately negotiated. The system works fine.

But now a group of provider A’s, who may not want to build large amounts of new network capacity to meet rising demand for mobile data, like video, Facebook, Twitter, and app downloads, etc., want the FCC to mandate access to B’s networks at regulated prices. And in this case, the B’s have spent many tens of billions of dollars in spectrum and network equipment to provide fast data services, though even these investments can barely keep up with blazing demand. . . .

It is perhaps not surprising that a small number of service providers who don’t invest as much in high-capacity networks might wish to gain artificially cheap access to the networks of the companies who invest tens of billions of dollars per year in their mobile networks alone. Who doesn’t like lower input prices? Who doesn’t like his competitors to do the heavy lifting and surf in his wake? But the also not surprising result of such a policy could be to reduce the amount that everyone invests in new networks. And this is simply an outcome the technology industry, and the entire country, cannot afford. The FCC itself has said that “broadband is the great infrastructure challenge of the early 21st century.”

But if Washington actually wants more infrastructure investment, it has a funny way of showing it. On Sunday at a Boston conference organized by Free Press, former Obama White House technology advisor Susan Crawford talked about America’s major communications companies. “[R]egulating these guys into to an inch of their life is exactly what needs to happen,” she said. You’d think the topic was tobacco or human trafficking rather than the companies that have pretty successfully brought us the wonders of the Internet.

It’s the view of an academic lawyer who has never visited that exotic place called the real world. Does she think that the management, boards, and investors of these companies will continue to fund massive infrastructure projects in the tens of billions of dollars if Washington dangles them within “an inch of their life”? Investment would dry up long before we ever saw the precipice. This is exactly what’s happened economy-wide over the last few years as every company, every investor, in every industry worried about Washington marching them off the cost cliff. The White House supposedly has a newfound appreciation for the harms of over-regulation and has vowed to rein in the regulators. But in case after case, it continues to toss more regulatory pebbles into the economic river.

Perhaps Nick Schulz of the American Enterprise Institute has it right. Take a look. He calls it the Tommy Boy theory of regulation, and just maybe it explains Washington’s obsession — yes, obsession; when you watch the video, you will note that is the correct word — with managing every nook and cranny of the economy.

Akamai CEO Exposes FCC’s Confused “Paid Priority” Prohibition

In the wake of the FCC’s net neutrality Order, published on December 23, several of us have focused on the Commission’s confused and contradictory treatment of “paid prioritization.” In the Order, the FCC explicitly permits some forms of paid priority on the Internet but strongly discourages other forms.

From the beginning — that is, since the advent of the net neutrality concept early last decade — I argued that a strict neutrality regime would have outlawed, among other important technologies, CDNs, which prioritized traffic and made (make!) the Web video revolution possible.

So I took particular notice of this new interview (sub. required) with Akamai CEO Paul Sagan in the February 2011 issue of MIT’s Technology Review:

TR: You’re making copies of videos and other Web content and distributing them from strategic points, on the fly.

Paul Sagan: Or routes that are picked on the fly, to route around problematic conditions in real time. You could use Boston [as an analogy]. How do you want to cross the Charles to, say, go to Fenway from Cambridge? There are a lot of bridges you can take. The Internet protocol, though, would probably always tell you to take the Mass. Ave. bridge, or the BU Bridge, which is under construction right now and is the wrong answer. But it would just keep trying. The Internet can’t ever figure that out — it doesn’t. And we do.

There it is. Akamai and other content delivery networks (CDNs), including Google, which has built its own CDN-like network, “route around” “the Internet,” which “can’t ever figure . . . out” the fastest path needed for robust packet delivery. And they do so for a price. In other words: paid priority. Content companies, edge innovators, basement bloggers, and poor non-profits who don’t pay don’t get the advantages of CDN fast lanes. (more…)

The Internet Survives, and Thrives, For Now

See my analysis of the FCC’s new “net neutrality” policy at RealClearMarkets:

Despite the Federal Communications Commission’s “net neutrality” announcement this week, the American Internet economy is likely to survive and thrive. That’s because the new proposal offered by FCC chairman Julius Genachowski is lacking almost all the worst ideas considered over the last few years. No one has warned more persistently than I against the dangers of over-regulating the Internet in the name of “net neutrality.”

In a better world, policy makers would heed my friend Andy Kessler’s advice to shutter the FCC. But back on earth this new compromise should, for the near-term at least, cap Washington’s mischief in the digital realm.

. . .

The Level 3-Comcast clash showed what many of us have said all along: “net neutrality” was a purposely ill-defined catch-all for any grievance in the digital realm. No more. With the FCC offering some definition, however imperfect, businesses will now mostly have to slug it out in a dynamic and tumultuous technology arena, instead of running to the press and politicians.

Caveats. Already!

If it’s true, as Nick Schulz notes, that FCC Commissioner Copps and others really think Chairman Genachowski’s proposal today “is the beginning . . . not the end,” then all bets are off. The whole point is to relieve the overhanging regulatory threat so we can all move forward. More — much more, I suspect — to come . . . .

FCC Proposal Not Terrible. Internet Likely to Survive and Thrive.

The FCC appears to have taken the worst proposals for regulating the Internet off the table. This is good news for an already healthy sector. And given info-tech’s huge share of U.S. investment, it’s good news for the American economy as a whole, which needs all the help it can get.

In a speech this morning, FCC chair Julius Genachowski outlined a proposal he hopes the other commissioners will approve at their December 21 meeting. The proposal, which comes more than a year after the FCC issued its Notice of Proposed Rule Making into “Preserving the Open Internet,” appears mostly to codify the “Four Principles” that were agreed to by all parties five years ago. Namely:

- No blocking of lawful data, websites, applications, services, or attached devices.

- Transparency. Consumers should know what the services and policies of their providers are, and what they mean.

- A prohibition of “unreasonable discrimination,” which essentially means service providers must offer their products at similar rates and terms to similarly situated customers.

- Importantly, broadband providers can manage their networks and use new technologies to provide fast, robust services. Also, there appears to be even more flexibility for wireless networks, though we don’t yet know the details.

(All the broad-brush concepts outlined today will need closer scrutiny when detailed language is unveiled, and as with every government regulation, implementation and enforcement can always yield unpredictable results. One also must worry about precedent and a new platform for future regulation. Even if today’s proposal isn’t too harmful, does the new framework open a regulatory can of worms?)

So, what appears to be off the table? Most of the worst proposals that have been flying around over the last year, like . . .

- Reclassification of broadband as an old “telecom service” under Title II of the Communications Act of 1934, which could have pierced the no-government seal on the Internet in a very damaging way, unleashing all kinds of complex and antiquated rules on the modern Net.

- Price controls.

- Rigid nondiscrimination rules that would have barred important network technologies and business models.

- Bans of quality-of-service technologies and techniques (QoS), tiered pricing, or voluntary relationships between ISPs and content/application/service (CAS) providers.

- Open access mandates, requiring networks to share their assets.

Many of us have long questioned whether formal government action in this arena is necessary. The Internet ecosystem is healthy. It’s growing and generating an almost dizzying array of new products and services on diverse networks and devices. Communications networks are more open than ever. Facebook on your BlackBerry. Netflix on your iPad. Twitter on your TV. The oft-cited world broadband comparisons, which say the U.S. ranks 15h, or even 26th, are misleading. Those reports mostly measure household size, not broadband health. Using new data from Cisco, we estimate the U.S. generates and consumes more network traffic per user and per capita than any nation but South Korea. (Canada and the U.S. are about equal.) American Internet use is twice that of many nations we are told far outpace the U.S. in broadband. Heavy-handed regulation would have severely depressed investment and innovation in a vibrant industry. All for nothing.

Lots of smart lawyers doubt the FCC has the authority to issue even the relatively modest rules it outlined today. They’re probably right, and the question will no doubt be litigated (yet again), if Congress does not act first. But with Congress now divided politically, the case remains that Mr. Genachowski’s proposal is likely the near-term ceiling on regulation. Policy might get better than today’s proposal, but it’s not likely to get any worse. From what I see today, that’s a win for the Internet, and for the U.S. economy.

— Bret Swanson

The End of Net Neutrality?

In what may be the final round of comments in the Federal Communications Commission’s Net Neutrality inquiry, I offered some closing thoughts, including:

- Does the U.S. really rank 15th — or even 26th — in the world in broadband? No.

- The U.S. generates and consumes substantially more IP traffic per Internet user and per capita than any other region of the world.

- Among individual nations, only South Korea generates significantly more IP traffic than the U.S. (Canada and the U.S. are equal.)

- U.S. wired and wireless broadband networks are among the world’s most advanced, and the U.S. Internet ecosystem is healthy and vibrant.

- Latency is increasingly important, as demonstrated by a young company called Spread Networks, which built a new optical fiber route from Chicago to New York to shave mere milliseconds off the existing fastest network offerings. This example shows the importance — and legitimacy — of “paid prioritization.”

- As we wrote: “One way to achieve better service is to deploy more capacity on certain links. But capacity is not always the problem. As Spread shows, another way to achieve better service is to build an entirely new 750-mile fiber route through mountains to minimize laser light delay. Or we might deploy a network of server caches that store non-realtime data closer to the end points of networks, as many Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) have done. But when we can’t build a new fiber route or store data — say, when we need to get real-time packets from point to pointover the existing network — yet another option might be to route packets more efficiently with sophisticated QoS technologies.”

- Exempting “wireless” from any Net Neutrality rules is necessary but not sufficient to protect robust service and innovation in the wireless arena.

- “The number of Wi-Fi and femtocell nodes will only continue to grow. It is important that they do, so that we might offload a substantial portion of traffic from our mobile cell sites and thus improve service for users in mobile environments. We will expect our wireless devices to achieve nearly the robustness and capacity of our wired devices. But for this to happen, our wireless and wired networks will often have to be integrated and optimized. Wireline backhaul — whether from the cell site or via a residential or office broadband connection — may require special prioritization to offset the inherent deficiencies of wireless. Already, wireline broadband companies are prioritizing femtocell traffic, and such practices will only grow. If such wireline prioritization is restricted, crucial new wireless connectivity and services could falter or slow.”

- The same goes for “specialized services,” which some suggest be exempted from new Net Neutrality regulations. Again, necessary but not sufficient.

- “Regulating the ‘basic’ Internet but not ‘specialized’ services will surely push most of the network and application innovation and investment into the unregulated sphere. A ‘specialized’ exemption, although far preferable to a Net Neutrality world without such an exemption, would tend to incentivize both CAS providers and ISPs service providers to target the ‘specialized’ category and thus shrink the scope of the ‘open Internet.’ In fact, although specialized services should and will exist, they often will interact with or be based on the ‘basic’ Internet. Finding demarcation lines will be difficult if not impossible. In a world of vast overlap, convergence, integration, and modularity, attempting to decide what is and is not ‘the Internet’ is probably futile and counterproductive. The very genius of the Internet is its ability to connect to, absorb, accommodate, and spawn new networks, applications and services. In a great compliment to its virtues, the definition of the Internet is constantly changing.”

The Regulatory Threat to Web Video

See our commentary at Forbes.com, responding to Revision3 CEO Jim Louderback’s calls for Internet regulation.

What we have here is “mission creep.” First, Net Neutrality was about an “open Internet” where no websites were blocked or degraded. But as soon as the whole industry agreed to these perfectly reasonable Open Web principles, Net Neutrality became an exercise in micromanagement of network technologies and broadband business plans. Now, Louderback wants to go even further and regulate prices. But there’s still more! He also wants to regulate the products that broadband providers can offer.

“In the Matter of Preserving the Open Internet”

Here were my comments in the FCC’s Notice of Proposed Rule Making on “Preserving the Open Internet” — better known as “Net Neutrality”:

A Net Neutrality regime will not make the Internet more “open.” The Internet is already very open. More people create and access more content and applications than ever before. And with the existing Four Principles in place, the Internet will remain open. In fact, a Net Neutrality regime could close off large portions of the Internet for many consumers. By intruding in technical infrastructure decisions and discouraging investment, Net Neutrality could decrease network capacity, connectivity, and robustness; it could increase prices; it could slow the cycle of innovation; and thus shut the window to the Web on millions of consumers. Net Neutrality is not about openness. It is far more accurate to say it is about closing off experimentation, innovation, and opportunity.

A Victory For the Free Web

After yesterday’s federal court ruling against the FCC’s overreaching net neutrality regulations, which we have dedicated considerable time and effort combatting for the last seven years, Holman Jenkins says it well:

Hooray. We live in a nation of laws and elected leaders, not a nation of unelected leaders making up rules for the rest of us as they go along, whether in response to besieging lobbyists or the latest bandwagon circling the block hauled by Washington’s permanent “public interest” community.

This was the reassuring message yesterday from the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals aimed at the Federal Communications Commission. Bottom line: The FCC can abandon its ideological pursuit of the “net neutrality” bogeyman, and get on with making the world safe for the iPad.

The court ruled in considerable detail that there’s no statutory basis for the FCC’s ambition to annex the Internet, which has grown and thrived under nobody’s control.

. . .

So rather than focusing on new excuses to mess with network providers, the FCC should tackle two duties unambiguously before it: Figure out how to liberate the nation’s wireless spectrum (over which it has clear statutory authority) to flow to more market-oriented uses, whether broadband or broadcast, while also making sure taxpayers get adequately paid as the current system of licensed TV and radio spectrum inevitably evolves into something else.

Second: Under its media ownership hat, admit that such regulation, which inhibits the merger of TV stations with each other and with newspapers, is disastrously hindering our nation’s news-reporting resources and brands from reshaping themselves to meet the opportunities and challenges of the digital age. (Willy nilly, this would also help solve the spectrum problem as broadcasters voluntarily redeployed theirs to more profitable uses.)

More wireless connectivity? Or more politics?

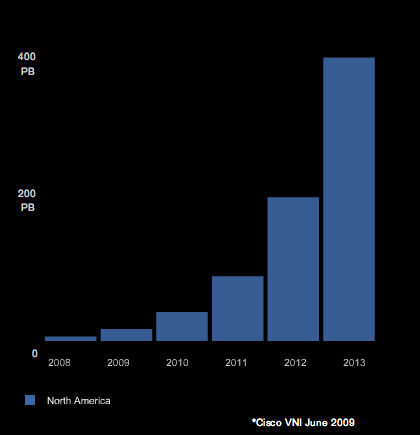

For years we’ve been talking about the need for more wireless bandwidth, more spectrum, and a host of creative new strategies to complement our mobile phone networks — from familiar Wi-Fi to more exotic femtocells and satellites. The continuing explosion of mobile data traffic means we need these things now more than ever. In the graph below, Cisco projects 120% compound annual growth in North American mobile data from 2009 through 2013.

The Federal Communications Commission recognized these trends and needs in its new National Broadband Plan. It set the bold goal of unleashing 500 MHz of mostly dormant wireless spectrum for more productive use in new broadband Internet and media applications.

On March 29, the FCC had a chance to begin putting its Plan into action when it approved the acquisition of SkyTerra by Harbinger Capital. The result of the merger is a new wireless company that will use both MSS satellite spectrum and so-called ATC terrestrial spectrum to deliver a new hybrid mobile service. Harbinger announced it would build a nationwide, wholesale, “open access” 4G broadband wireless network at the cost of $6 billion. Although not part of the FCC’s 500 MHz push, the new Harbinger strategy aligns nicely with the goal of more, better, and broader wireless access and options throughout the country (in this case, Canada, too).

But the FCC order, which was not voted by the full commission but issued by the bureau chiefs, contains two curious provisions. The provisions restrict Harbinger’s cooperation with two important mobile service providers and could hinder the very goal of extending more wireless coverage to more Americans. (more…)

Quote of the Day

“Architects of the legislation that binds the nation’s communications infrastructure in the year 2010 were born in the 1870s and 1880s. There is talk today in Washington about categorizing technologies and platforms developed in the 21st century under different Titles of legislation written by people born in the 19th century. We don’t need to jettison all the wisdom of the ancients, but perhaps there’s a better way?”

— Nick Shulz, at the Enterprise Blog, March 25, 2010

Washington liabilities vs. innovative assets

Our new article at RealClearMarkets:

As Washington and the states pile up mountainous liabilities — $3 trillion for unfunded state pensions, $10 trillion in new federal deficits through 2019, and $38 trillion (or is it $50 trillion?) in unfunded Medicare promises — the U.S. needs once again to call on its chief strategic asset: radical innovation.

One laboratory of growth will continue to be the Internet. The U.S. began the 2000’s with fewer than five million residential broadband lines and zero mobile broadband. We begin the new decade with 71 million residential lines and 300 million portable and mobile broadband devices. In all, consumer bandwidth grew almost 15,000%.

Even a thriving Internet, however, cannot escape Washington’s eager eye. As the Federal Communications Commission contemplates new “network neutrality” regulation and even a return to “Title II” telephone regulation, we have to wonder where growth will come from in the 2010’s . . . .

Did the FCC get the White House jobs memo?

That’s the question I ask in this Huffington Post article today.