[W]e have these big agencies, some of which are outdated, some of which are not designed properly . . . . The White House is just a tiny part of what is a huge, widespread organization with increasingly complex tasks in a complex world.

That was President Obama, last week, explaining Obamacare’s failed launch. We couldn’t have said it better ourselves.

Where Washington thinks this is a reason to give itself more to do, with more resources, however, we see it as a blaring signal of overreach.

The Administration now says Healthcare.gov is operating with “private sector velocity and effectiveness.” But why seek to further governmentalize one-seventh of the economy if the private sector is faster and more effective than government?

Meanwhile, the New York Times notes that

The technology troubles that plagued the HealthCare.gov website rollout, may not have come as a shock to people who work for certain agencies of the government — especially those who still use floppy disks, the cutting-edge technology of the 1980s.

Every day, The Federal Register, the daily journal of the United States government, publishes on its website and in a thick booklet around 100 executive orders, proclamations, proposed rule changes and other government notices that federal agencies are mandated to submit for public inspection.

So far, so good.

It turns out, however, that the Federal Register employees who take in the information for publication from across the government still receive some of it on the 3.5-inch plastic storage squares that have become all but obsolete in the United States.

Floppy disks make us chuckle. But the costs of complexity are all too real.

A Bloomberg study found the six largest U.S. banks, between 2008 and August of this year, spent $103 billion on lawyers and related legal expenses. These costs pale compared to the far larger economic distortions imposed by metastasizing financial regulation. Even Barney Frank is questioning whether his signature law, Dodd-Frank, is a good idea. The bureaucracy’s decision to push regulations intended for big banks onto money managers and mutual funds seems to have tipped his thinking.

This is not an aberration. This is what happens with vast, complex, ambiguous laws, which ask “huge, widespread” bureaucracies to implement them.

It is the norm of today’s sprawling Administrative State and of Congress’s penchant for 2,000-page wish lists, which ineluctably empower that Administrative State.

We resist, however, the idea that the problem is merely “outdated” or “inefficient” bureaucracy.

We do not need better people to administer these “laws.” With laws and regulations this extensive and ambiguous, they are inherently political. The best managers would seek efficient and effective outcomes based on common-sense readings and would resist political tampering. Effective implementation of conflicting and economically irrational rules would still yield big problems. Regardless, the goal is not effective management — it is political control.

Agency “reform” is not the answer, although in most cases reform is preferable to no reform. Even reformed agencies do not possess the information to manage a “complex world.” Anyway, “competent” management is not what the political branches want. Agencies routinely evade existing controls — such as procurement rules — when convenient. The largest Healthcare.gov contractor, for example, reportedly got the work without any contesting bids. That is not an oversight, it is a decision.

The laws and rules are uninterpretable by the courts. Depending on which judges hear the cases, we get dramatically and unpredictably divergent analyses, or the type of baby splitting Chief Justice Roberts gave us on Obamacare. Judges thus end up either making their own law or throwing the question back into the political arena.

Infinite complexity of law means there is no law.

“With great power,” Peter Parker’s (aka Spiderman’s) uncle told us, “comes great responsibility.” For Washington, however, ambiguity and complexity are features, not bugs. Ambiguity and complexity promote control without accountability, power without responsibility.

The only solution to this crisis of complexity is to reform the very laws, rules, scope, and aims of government itself.

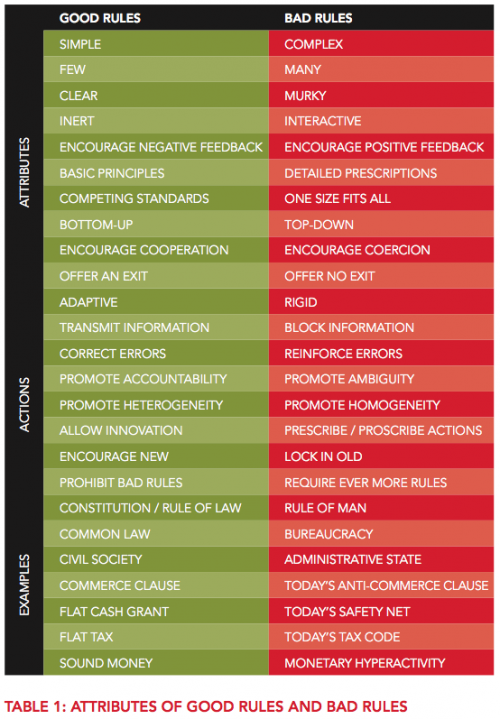

In a paper last spring called “Keep It Simple,” we highlighted two instances — one from the labor markets and one from the capital markets — where even the most well-intended rules yielded catastrophic results. We showed how the interactions among these rules and the supporting bureaucracies produced unintended consequences. And we outlined a basic framework for assessing “good rules and bad rules.”

As our motto and objective, we adopted Richard Epstein’s aspiration of “simple rules for a complex world.” Which, you will notice, is the just opposite of the problem so incisively outlined by the President — Washington’s failed attempts to perform “complex tasks in a complex world.”

As we wrote elsewhere,

The private sector is good at mastering complexity and turning it into apparent simplicity — it’s the essence of wealth creation. At its best, the government is a neutral arbiter of basic rules. The Administration says it is ‘discovering’ how these ‘complicated’ things can blow up. We’ll see if government is capable of learning.