The complexities of the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare) are multiple, metastasizing, and increasingly well-known. Less known is an additional layer of health care regulation slated for implementation next year: the system by which doctors and hospitals code for conditions, injuries, and treatments. By way of illustration, in the old system, a broken arm might get the code 156; pneumonia might be 397. The new system is much more advanced. As Ben Domenech notes:

- The new codes account for injury sites, ranging from opera houses to chicken coops to squash courts.

- One code is for “burn due to water-skis on fire” and another for “walked into lamppost.”

- The codes are so nuanced that “bitten by turtle” and “struck by turtle” are separate codes.

- There are a total of nine codes strictly pertaining to injuries that occur in and around a mobile home.

- There are 72 codes pertaining to birds and 312 codes related to animals.

- There’s even a code for civilian drone strikes.

In all, the new system, known as ICD-10, will boast 140,000 codes, a near-eight-fold rise over the mere 18,000 codes in ICD-9. It is a good example of the way bureaucracies grow in size and complexity in an attempt to match the complexity of society and the economy. This temptation, however, is usually perverse.

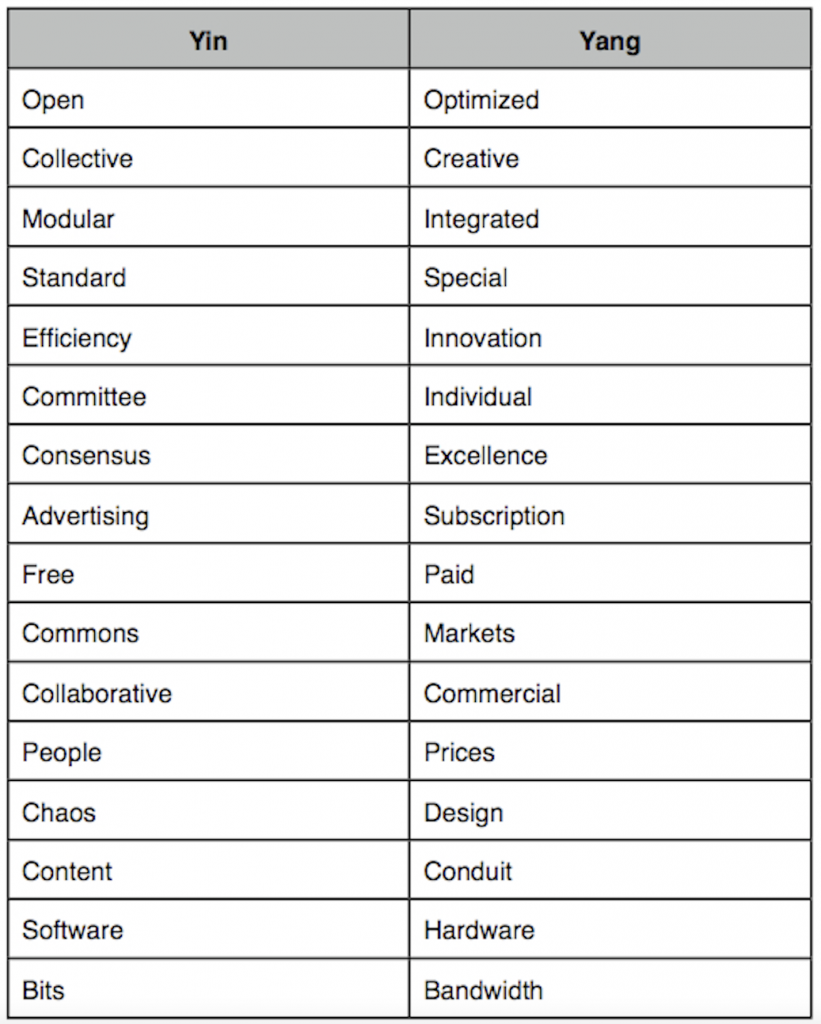

Complexity in the economy means new technologies, more specialized goods and services, and more consumer and vocational choice. Economic complexity, however, is built upon a foundation of simplicity – clear, basic rules and institutions. Simple rules encourage experimentation, promote long-term investments and entrepreneurial ventures, and allow the flexibility to drive and accommodate diversity.

Complex rules, on the other hand, often lead to just the opposite: less experimentation, investment, entrepreneurship, diversity, and choice.

It is difficult to quantify the effects of the metastasizing Administrative State. It is impossible to calculate, say, the cost of regulations that prohibit, discourage, or delay innovation. Likewise, what is the cost of the regulations that, arguably, helped cause the Financial Panic of 2008 and its policy fallout? No one can say with precision. For twenty years, though, the Competitive Enterprise Institute has catalogued regulatory complexity as well as anyone, and its latest report is astonishing.

Federal regulation, CEI’s latest “10,000 Commandments” survey finds, costs the U.S. economy some $1.8 trillion annually. That’s more than 10% of GDP, or nearly $15,000 per citizen. These estimates largely predate the implementation of the ACA, Dodd-Frank, and new rounds of EPA intervention. In other words, it’s only getting worse.

The legal scholar Richard Epstein argues that

The dismal performance of the IRS is but a symptom of a much larger disease which has taken root in the charters of many of the major administrative agencies in the United States today: the permit power. Private individuals are not allowed to engage in certain activities or to claim certain benefits without the approval of some major government agency. The standards for approval are nebulous at best, which makes it hard for any outside reviewer to overturn the agency’s decision on a particular application.

That power also gives the agency discretion to drag out its review, since few individuals or groups are foolhardy enough to jump the gun and set up shop without obtaining the necessary approvals first. It takes literally a few minutes for a skilled government administrator to demand information that costs millions of dollars to collect and that can tie up a project for years. That delay becomes even longer for projects that need approval from multiple agencies at the federal or state level, or both.

The beauty of all of this (for the government) is that there is no effective legal remedy. Any lawsuit that protests the improper government delay only delays the matter more. Worse still, it also invites that agency (and other agencies with which it has good relations) to slow down the clock on any other applications that the same party brings to the table. Faced with this unappetizing scenario, most sophisticated applicants prefer quiet diplomacy to frontal assault, especially if their solid connections or campaign contributions might expedite the application process. Every eager applicant may also be stymied by astute competitors intent on slowing the approval process down, in order to protect their own financial profits. So more quiet diplomacy leads to further social waste.

Epstein argues the FDA, EPA, FCC, and other agencies all use this permit power to control firms, industries, and people beyond any reasonable belief they are providing a net benefit to society.

The agencies are guilty of overreach and promoting their own metastasis. Yet without Congress and the President, they would have little or no power. Congresses and Presidents increasingly pass thousand-page laws that ask agencies to produce tens of thousands of pages of attendant rules and regulations. Complexity grows. Accountability is lost. The economy suffers. And the corrective paths, which fix mistakes and promote renewal in the rest of the economy and society, are blocked. We then pile on tomorrow’s complexity to “fix” the flaws created by yesterday’s complexity.

The hyper-regulation of the economy is not merely an annoyance, not merely about inefficient paperwork. It is damaging our innovative and productive capacity — and thus employment, the budget, and our standard of living.

The McKinsey Global Institute helps us understand why this matters from a macro perspective. McKinsey chose a dozen existing and emerging technologies and estimated their potential economic impact in the year 2025. It found industries like the mobile Internet, cloud computing, self-driving cars, and genomics could produce economic benefits of up to $33 trillion worldwide. The operative word, however, is “might.” Innovation is all about what’s new. And regulation is often about disallowing or discouraging what’s new. The growing complexity of the regulatory state, therefore, can only block some number of these innovations and is thus likely to leave us with a simpler, and thus poorer, world.

— Bret Swanson