FCC chairman Julius Genachowski opens a new op-ed with a bang:

As Washington continues to wrangle over raising revenue and cutting spending, let’s not forget a crucial third element for reining in the deficit: economic growth. To sustain long-term economic health, America needs growth engines, areas of the economy that hold real promise of major expansion. Few sectors have more job-creating innovation potential than broadband, particularly mobile broadband.

Private-sector innovation in mobile broadband has been extraordinary. But maintaining the creative momentum in wireless networks, devices and apps will need an equally innovative wireless policy, or jobs and growth will be left on the table.

Economic growth is indeed the crucial missing link to employment, opportunity, and healthier government budgets. Technology is the key driver of long term growth, and even during the downturn the broadband economy has delivered. Michael Mandel estimates the “app economy,” for example, has created more than 500,000 jobs in less than five short years of existence.

We emphatically do need policies that will facilitate the next wave of digital innovation and growth. Chairman Genachowski’s top line assessment — that U.S. broadband is a success — is important. It rebuts the many false but persistent claims that U.S. broadband lags the world. Chairman Genachowski’s diagnosis of how we got here and his prescriptions for the future, however, are off the mark.

For example, he suggests U.S. mobile innovation is newer than it really is.

Over the past few years, after trailing Europe and Asia in mobile infrastructure and innovation, the U.S. has regained global leadership in mobile technology.

This American mobile resurgence did not take place in just the last “few years.” It began a little more than decade ago with smart decisions to:

(1) allow reasonable industry consolidation and relatively free spectrum allocation, after years of forced “competition,” which mandated network duplication and thus underinvestment in coverage and speed (we did in fact trail Europe in some important mobile metrics in the late 1990s and briefly into the 2000s);

(2) refrain from any but the most basic regulation of broadband in general and the mobile market in particular, encouraging experimental innovation; and

(3) finally implement the digital TV / 700 MHz transition in 2007, which put more of the best spectrum into the market.

These policies, among others, encouraged some $165 billion in mobile capital investment between 2001 and 2008 and launched a wave of mobile innovation. Development on the iPhone began in 2004, the iPhone itself arrived in 2007, and the app store in 2008. Google’s Android mobile OS came along in 2009, the year Mr. Genachowski arrived at the FCC. By this time, the American mobile juggernaut had already been in full flight for years, and the foundation was set — the U.S. topped the world in 3G mobile networks and device and software innovation. Wi-Fi, meanwhile surged from 2003 onward, creating an organic network of tens of millions of wireless nodes in homes, offices, and public spaces. Mr. Genachowski gets some points for not impeding the market as aggressively as some other more zealous regulators might have. But taking credit for America’s mobile miracle smacks of the rooster proudly puffing his chest at sunrise.

More important than who gets the credit, however, is determining what policies led to the current success . . . and which are likely to spur future growth. Chairman Genachowski is right to herald the incentive auctions that could unleash hundreds of megahertz of un- and under-used spectrum from the old TV broadcasters. Yet wrangling over the rules of the auctions could stretch on, delaying the the process. Worse, the rules themselves could restrict who can bid on or buy new spectrum, effectively allowing the FCC to favor certain firms, technologies, or friends at the expense of the best spectrum allocation. We’ve seen before that centrally planned spectrum allocations don’t work. The fact that the FCC is contemplating such an approach is worrisome. It runs counter to the policies that led to today’s mobile success.

The FCC also has a bad habit of changing the metrics and the rules in the middle of the game. For example, the FCC has been caught changing its “spectrum screen” to fit its needs. The screen attempts to show how much spectrum mobile operators hold in particular markets. During M&A reviews, however, the FCC has changed its screen procedures to make the data fit its opinion.

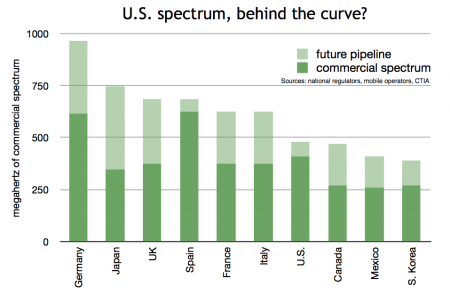

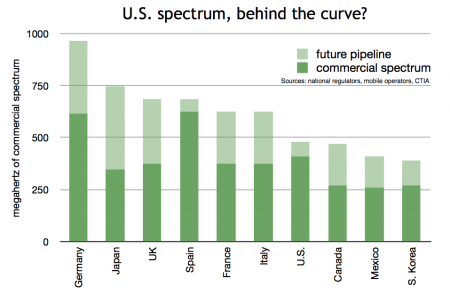

In a more recent example, Fred Campbell shows that the FCC alters its count of total available commercial spectrum to fit the argument it wants to make from day to day. We’ve shown that the U.S. trails other nations in the sum of currently available spectrum plus spectrum in the pipeline. Below, see a chart from last year showing how the U.S. compares favorably in existing commercially available spectrum but trails severely in pipeline spectrum. Translation: the U.S. did a pretty good job unleashing spectrum in 1990s through he mid-2000s. But, contrary to Chairman Genachowski’s implication, it has stalled in the last few years.

When the FCC wants to argue that particular companies shouldn’t be allowed to acquire more spectrum (whether through merger or secondary markets), it adopts this view that the U.S. trails in spectrum allocation. Yet when challenged on the more general point that the U.S. lags other nations, the FCC turns around and includes an extra 139 MHz in spectrum in the 2.5 GHz range to avoid the charge it’s fallen behind the curve.

Next, Chairman Genachowski heralds a new spectrum “sharing” policy where private companies would be allowed to access tiny portions of government-owned airwaves. This really is weak tea. The government, depending on how you measure, controls between 60% and 85% of the best spectrum for wireless broadband. It uses very little of it. Yet it refuses to part with meaningful portions, even though it would still be left with more than enough for its important uses — military and otherwise. If they can make it work (I’m skeptical), sharing may offer a marginal benefit. But it does not remotely fit the scale of the challenge.

Along the way, the FCC has been whittling away at mobile’s incentives for investment and its environment of experimentation. Chairman Genachowski, for example, imposed price controls on “data roaming,” even though it’s highly questionable he had the legal authority to do so. The Commission has also, with varied degrees of “success,” been attempting to impose its extralegal net neutrality framework to wireless. And of course the FCC has blocked, altered, and/or discouraged a number of important wireless mergers and secondary spectrum transactions.

Chairman Genachowski’s big picture is a pretty one: broadband innovation is key to economic growth. Look at the brush strokes, however, and there are reasons to believe sloppy and overanxious regulators are threatening to diminish America’s mobile masterpiece.

— Bret Swanson