“It is the single worst telecom bill that I have ever seen.”

— Reed Hundt, Jan. 31, 2012

Isn’t this rich?

One of the most zealous regulators America has known says Congress is overstepping its bounds because it wants to unleash lots of new wireless spectrum but also wants to erect a few guardrails so that FCC regulators don’t run roughshod over the booming mobile broadband market.

At a New America Foundation event yesterday, former FCC chairman Reed Hundt said Congress shouldn’t micromanage the FCC’s ability to micromanage the wireless industry. Mr. Congressman, you don’t know anything about how the FCC should regulate the Internet. But the FCC does know how to build networks, run mobile Internet businesses, and perfectly structure a wildly tumultuous economic sector. It’s just the latest remarkable example of the growing hubris of the regulatory state.

In his book, You Say You Want a Revolution, Hundt famously recounted his staff’s interpretation and implementation of the 1996 Telecom Act.

The passage of the new law placed me on a far more public stage. But I felt Congress — in the constitutional sense — had asked me to exercise the full power of all ideas I could summon. And I believed that I and my team had learned, through many failures, how to succeed. Later, I realized that we knew almost nothing of the complexity and importance of the tasks in front of the FCC.

…

Meeting in several overlapping groups of about a dozen people each . . . we dedicated almost three weeks to studying the possible readings of each word in the 150-page statute. The conference committee compromises had produced a mountain of ambiguity that was generally tilted toward the local phone companies’ advantage. But under the principles of statutory interpretation, we had broad authority to exercise our discretion in writing the implementing regulations. Indeed, like the modern engineers trying to straighten the Leaning Tower of Pisa, we could aspire to provide the new entrants to the local telephone markets a fairer chance to compete than they might find in any explicit provision of the law. In addition, the law gave almost no guidance about how to treat the Internet, data networks, . . . and many other critical issues. (Three years later, Justice Antonin Scalia agreed, on behalf of the Supreme Court, that the law was profoundly ambiguous.)

…

The more my team studied the law, the more we realized our decisions could determine the winners and losers of the new economy. We did not want to confer advantage on particular companies; that seemed inequitable. But inevitably

wink, wink,

a decision that promoted entry into the local market would benefit a company that followed such a strategy.

There are so many angles here.

(1) Hundt says he and his team basically stretched the statute to mean whatever they wanted. The law may have been ambiguous — and it was, I’m not going to defend the ’96 Act — yet the Supreme Court still found in a series of early-2000s cases that Hundt’s FCC had wildly overstepped even these flimsy bounds. That’s how aggressive and unconstrained Hundt was.

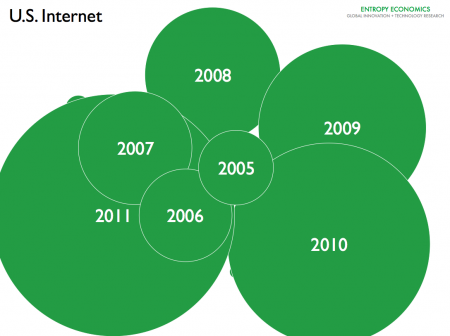

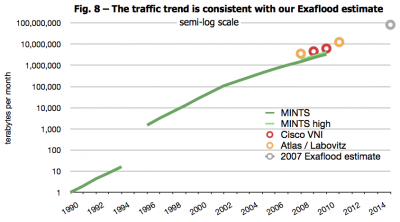

(2) Hundt’s rules helped crash the tech and telecom sectors in 2000-2002. His rules were so complex and intrusive that, whatever your views about the CLEC wars, the PCS C block spectrum debacle, and other battles, it’s hard to deny that the paralysis caused by the rules hurt broadband and the nascent Net.

(3) Is it surprising that, given the FCC’s poor record of reaching way past its granted powers, some in Congress want to circumscribe FCC regulators by giving them less-than-omnipotent authority? Is the new view of elite regulators that Congress should pass laws, the full text of which might read: “§1. Congress grants to the Internet Agency the authority to regulate the Internet. Go forth and regulate.”

(4) On the other hand, it’s not clear why Hundt would care particularly what Congress says in any new spectrum statute. He didn’t care much for the words or intent of the ’96 Act, and he thinks regulators should “aspire” to grand self-appointed projects. Who knows, maybe all those Supreme Court smack downs in the early 2000s made an impression.

(5) Hundt says he and his team later realized, in effect, how naive they were about “the complexity and importance of the tasks in front of the FCC.” So he’s acknowledging after things didn’t go so well that his FCC underestimated the complexity and thus overestimated their own expertise . . . yet he says today’s FCC deserves comprehensive power to structure the mobile Internet as it sees fit?

(6) Hundt admitted his FCC relished its capacity to pick winners and losers. Not particular companies, mind you — that would be improper — merely the types of companies who win and lose. A distinction without very much of a difference.

(7) We don’t argue that Congress, instead of the FCC, should impose intrusive regulation through statute. We don’t advocate long and complex laws. That’s not the point. Laws should be clear and simple, but stating the boundaries of a regulator’s authority is not a controversial act. No one should be imposing intrusive regulation or overdetermining the structure of an industry. And that’s what Congress — perhaps in a rare case! — is protecting against here.